Alison Balsom is on a mission to elevate the trumpet soloist’s role.

By Damian Fowler

In November of last year, American talk-show host David Letterman heard a piece of music on his car radio that caught his attention. It was a track from a new album of Italian concertos played by trumpet virtuoso Alison Balsom. Perhaps it was the sparkling ease and technical brilliance with which Balsom delivered the baroque phrasings of the concerto, or perhaps it was the novelty of a young, female trumpet player that caught his attention. Whatever it was, Letterman invited the soloist to perform on The Late Show in December. “I was very honored,” says Balsom. “They rarely have classical musicians on the show.”

The thirty-two-year-old Englishwoman has a natural advantage when it comes to impressing audiences. A gifted player, she also happens to look stunning in a ball gown even as she wields her piccolo trumpet. On Letterman, she wowed the audience and the nonchalant host as she performed, in a sleek black dress, the third movement from Marcello’s Oboe Concerto in C minor with members of the St. Luke’s Orchestra.

Initially, Balsom considered playing something lighter, more popular, for the late-night audience, but then she thought, “No, that’s not what Letterman heard on the radio,” so she stuck to her guns and played the piece from her latest CD, Italian Concertos (EMI).

Against the odds, Balsom has carved out a career as a trumpet soloist and is now in demand on concert stages in Europe, the United States and Asia, performing with leading orchestras as a recitalist on Baroque and modern trumpets. She became a darling of the British press after winning British Female Artist of the Year at the 2009 Classical Brit Awards and then being invited to play for the Last Night of the Proms. Millions tuned in to the concert, which Balsom called “the gig of my life.”

She certainly has people’s attention, but for Balsom the challenge is to show the versatility and range of an instrument that has never been celebrated quite like those other show-offs, the violin or the piano. The fact that she’s a woman playing a brass instrument that in some quarters is still associated with the all-male colliery band is of secondary concern to her. “I started in my local brass band in Hertfordshire when I was seven,” she says. “I had the chance to play any instrument and I liked the look and the sound of the trumpet. It was quite an obvious choice. It was only when I got older when gender stereotypes started getting made.”

Certainly things have come a long way for female brass players over the last two decades. Julie Landsman, who recently retired after twenty-five years as the principal French horn for the Metropolitan Opera orchestra, recalls the famous story of her first blind audition with the Met. After she played — including an impressive, sustained high C — Landsman emerged from behind the curtain and remembers the audible gasps from the male judges when they realized she was a woman. She got the job.

Perhaps the bigger challenge for brass players is sustaining a career as a soloist. Great trumpet soloists, at least in the classical world, are few and far between. The great French trumpet player Maurice André, who rose to prominence in the 1960s and ’70s, opened up possibilities for the instrument with a large series of recordings of Baroque works. He also made many transcriptions for the trumpet of concertos for other instruments — oboe, flute and violin — to open up the limited repertoire. (Balsom’s Italian Concertos album includes popular concertos originally composed for the violin or oboe by Vivaldi, Tartini, Marcello, Albinoni and Cimarosa.) In fact, the limited repertoire for the instrument is one of the reasons carving out a career as a trumpet player has been such a difficult endeavor, with many players opting to take a seat in an orchestra as a principal player.

For Balsom, that has never been an option. As a schoolgirl, she fell in love with the sound of the trumpet from some Dizzy Gillespie records she got from her local library, even though she wasn’t playing jazz. Later, at the age of nine, she saw a performance at the Barbican by Håkan Hardenberger — the Swedish trumpet virtuoso — that convinced her to become a classical soloist. She cultivated her talent at the Junior Department of the Guildhall School of Music and eventually at the Paris Conservatoire, which has a strong tradition of developing trumpet soloists. Things came full circle when she started taking lessons from Hardenberger, who helped develop her sound. Her hard work paid off in 2000 when she won the prize for “Most Beautiful Sound” at the Maurice André International Trumpet Competition in Paris. That’s when she started to build her professional career with a debut CD (on EMI), released in 2002.

Top brass. ’People have yet to realize that the trumpet has so many colors,’ Balsom says.

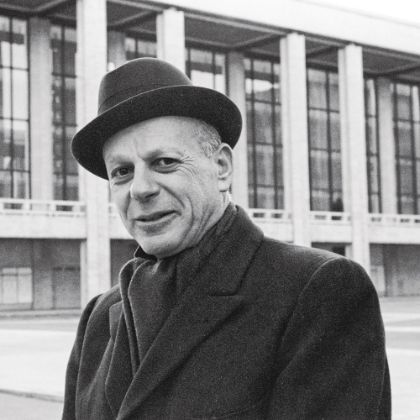

Mentor. Trumpeter Håkan Hardenberger inspired Alison Balsom at the age of nine to become a classical soloist; he would later become her teacher.

Even Hardenberger, widely held to be the greatest trumpet soloist of his generation, acknowledges the challenges of becoming a soloist. “When I was a kid, there were dreams after I heard Maurice André,” he says. “But you were told that’s not what you do. You play in an orchestra.” Hardenberger still remembers the moment when he accepted his destiny. He was an eighteen-year-old student playing Haydn’s Trumpet Concerto for a competition at the Philharmonie de Paris. After the cadenza in the first movement, the audience applauded. For Hardenberger it was “a magic second when I knew this is what I wanted to do.”

Perhaps the biggest hurdle for aspiring trumpet soloists is the lack of Romantic repertoire. There are staples from the Baroque and Classical periods — the Haydn and Hummel concertos being the most widely known and recorded — but there’s nothing by Beethoven, Brahms or Mahler. By the time the modern valve trumpet had been perfected, the Romantic master composers were dead. What’s a poor trumpet soloist to do?

One answer is to commission new work. “It very soon became clear to me we needed absolutely top-quality pieces,” says Hardenberger. “Why on earth would a symphony orchestra choose to play a second-rate trumpet concerto?” Hardenberger says he has spent the last thirty years trying to broaden the trumpet repertoire, commissioning works by composers such as Harrison Birtwistle, Hans Werner Henze, Rolf Martinsson, Mark-Anthony Turnage, Heinz Karl Gruber and Arvo Pärt.

Some of these composers have created signature pieces; Gruber’s Aerial, which Hardenberger has performed more than fifty times, comes to mind. The trumpeter, who shared many of his virtuosic techniques with Gruber as the composer was writing the piece, jokes that he gets gray hairs when he has to play it. But he’s only got himself to blame. “Anyway, I don’t have five Beethoven pieces I can choose from,” he says. In 2010 Hardenberger premiered Gruber’s second trumpet concerto, Busking, which was inspired by Picasso’s painting Three Musicians and features a trumpet soloist, an accordion and a banjo accompanied by a classical string orchestra. Hardenberger calls it “the ill-behaved little brother of Aerial.”

Balsom, for her part, has inherited her former mentor’s commissioning zeal. In February of 2011 she performed the world premiere of James MacMillan’s Seraph, a commission written for Balsom and the Scottish Ensemble. For this piece, Balsom was delighted to work closely with the composer. “It seems a shame when composers write without [performers] communicating with them,” she says. “I love to be able to say, ‘I want to sound like this.’”

While Balsom’s latest record is a celebration of the Baroque era and the sweet and subtle sounds of the piccolo trumpet (“the trumpet on The Beatles’ ‘Penny Lane’” is how Balsom introduces the instrument in concert), she is firmly grounded in twentieth-century repertoire. “The composers of the twentieth century started to understand the scope of the instrument,” she says. Trumpet soloists, it seems, have to look backwards and forwards at the same time. To be sure, Balsom has a wish list of composers with whom she’d like to work, including Mark-Anthony Turnage, Thomas Adès, Oliver Knussen and John Adams. She relishes the thought of what these modern masters could do for the trumpet. “People have yet to realize that the trumpet has so many colors,” she says.

Balsom also takes delight in taking works for other instruments and transcribing them for the trumpet. On her 2006 album, Caprice, which she recorded with the Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra and conductor Edward Gardner (now her partner, with whom she has a son, Charlie, born in 2010), she included Piazzolla’s celebrated Libertango as well as the fiendishly difficult Caprice No. 24 by Paganini.

Perhaps audiences are catching on: suddenly the classical trumpet is seen as more than just bombast and fanfare. At a recent concert in New York City, Balsom gave a concert featuring works for trumpet and piano, including a dark-inflected, far-from-accessible sonata by Hindemith. But the trumpeter, as she did for all the pieces, provided a succinct and impassioned introduction. The audience was with her all the way.

related...

-

Master Builder

His compatriots made institutions of their music. William Schuman made institutions.

Read More

By Russell Platt -

Back to Bach

Pianist András Schiff revisits The Well-Tempered Clavier and other totems of J.S. Bach — on stage and on record.

Read More

By Bradley Bambarger -

Evolution of Form

Everything you always wanted to know about Baroque concertos (but were afraid to ask)

Read More

By David Hurwitz