Bach and Bauhaus

Considering the fugues of an expressionist painter

By Monika S. Finane and Ben Finane

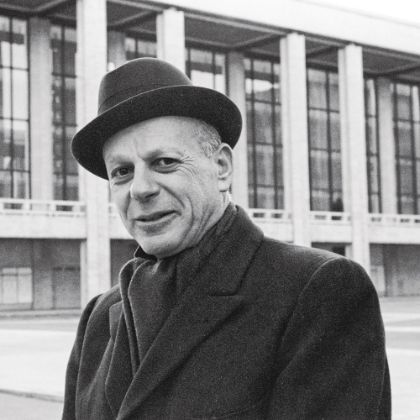

Born in New York in 1871 to an international concertizing violinist and an accomplished pianist, Lyonel Feininger seemed destined — by his German-American parents — to an ambitious musical career. Sent on an ocean liner to Germany to continue his study of the violin at the Leipzig Konservatorium (where his father had studied), the sixteen-year-old Lyonel literally jumped ship in Hamburg — as much to gain firm ground as to liberate himself from a musical path that had been all too well laid out for him.

Feininger instead immersed himself in his other talent, draftsmanship, and by the early 1900s had become a leading cartoonist, contributing to German periodicals as well as some American ones. (His Kin-der-Kids and Wee Willie Winkie’s World comic strips, created for the Chicago Sunday Tribune, are considered milestones of cartoon history.) Although Feininger was always considered “der Amerikaner,” he settled in Germany without ever taking trips home to the States until 1936, when he and his Jewish wife moved to New York in the face of rising Nazi oppression. By that time, Feininger was part of the leading group of avant-garde artists in Germany whose work was declared “degenerate” by the authorities.

Despite his success as an illustrator, for a long time Feininger had aspired to become a serious artist, namely a painter. His early paintings and watercolors were extravagant combinations of lanky figures in dreamlike old-world places filled with humor and whimsical nostalgia. Organized in distorted perspectives, stark color contrasts and contours, these paintings were at times crammed with figures. Next to Feininger’s matchless characters — his gentlemen in top hats, stumpy workers, questionable damsels or fierce churchmen — the occasional musician appeared. A tall loner playing a fiddle and a carnivalesque horde blowing trumpets are among the most memorable.

In Feininger’s work, music was not used as a mere gimmick. The artist, who continued to play the violin and often sat at his Estey reed organ, described his paintings as “sound contained.” In 1914 he declared in a letter to his wife, Julia: “The thirst for sound is powerful in me. . . . It is necessary for my very sustenance.” A few years later, in which time Feininger had both lived through the Great War (in its last year as an enemy alien) and also struggled to find his own way towards abstraction, the sound and sometimes roar of his early paintings had given way to a more mature tone. “When I was unable to paint, I played Bach; it was the only way to lull my troubles,” he wrote.

The music of Johann Sebastian Bach had long been an inspirational source for Feininger: he prized “the architectonic side of Bach, whereby a germinal idea is developed into a huge polyphonic form.” Feininger’s artistic approach became more and more structural. He worked on establishing a formal idea that would let him transform reality into something larger, even monumental, something “nearing closer to the synthesis of a fugue.”

Most of Feininger’s paintings were now stripped of all earlier narration and focused instead on single, simple motifs, such as a village church, that would dominate the canvas and set the overall theme. The color contrasts had become finely nuanced, directed by an intricate play of light and shade recalling Bach’s elaborate harmonic modulations. By 1919, the year Feininger became a founding master of the Bauhaus in Weimar, he had reached a highpoint in his work. His paintings were now complex compositions of great clarity, harmony and calm monumentality, where geometrical planes of translucent color were organized like overlapping voices harmonically echoing, modulating or inverting a simple theme — just as in a fugue.

Coined by leading art critics as “crystalline Cubism,” Feininger’s work hit a nerve of its time, the term invoking the prevailing notion of the crystal as a symbol of dematerialized spirituality. The crystal was further equated with abstraction, and by extension, the desire for the eternal. Feininger, who may not have disagreed with this characterization, was, as he was so often, more comfortable speaking in musical terms, and wrote in 1923: “Bach’s essence has found expression in my paintings.”

This time, Feininger was speaking from an even more musically informed angle. After being presented with an organ fugue for his fiftieth birthday by his son’s piano teacher, Feininger spent the next thirteen days composing a fugue of his own. Eleven more would follow until 1927, when his wife put an end to Feininger’s career as a composer, insisting that he return his focus to his painting, the production of which had dipped precipitously.

This past fall, in conjunction with “Lyonel Feininger: At the Edge of the World” at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art (curated by Barbara Haskell and now on view at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts until May 13), the American Symphony Orchestra, under the baton of its music director, Leon Botstein, performed a Carnegie Hall concert titled “Bauhaus Bach.” The program gave Bach a modernist bent, in the form of twentieth-century orchestrations by Arnold Schoenberg, Max Reger and others. The concert also featured performances of three of Lyonel Feininger’s fugues, with orchestration by Richard Wilson.

After seemingly dismissing Feininger’s fugues in pre-concert lecture as a “novelty,” Botstein recanted to Listen upon cross-examination. Feininger’s fugues, he said, were “remarkable, clearly inspired by Bach,” with a “multilayered quality” and “clashes of counterpoint.”

“What’s a professional composer anyway?” Botstein mused from the stage of Isaac Stern Auditorium, permitting his Bauhaus focus to expand. “Was Ives’ greatness accidental? A result of his ineptitude? Schoenberg was an amateur painter, and Feininger was a deeply literate student of music whose skill was,” he paused, “non-trivial. Feininger’s obsession with the fugal form,” Botstein concluded, “is what’s interesting here.”

Hearing three of the Feininger fugues, the artist’s Fugue in D seemed the most traditional of the three, well constructed and the closest to Bach pastiche. Fugue III was a bouncing gigue, given charming and cheeky orchestration by Wilson that leant on pizzicato strings and vibraphone. But Feininger’s Fugue IV was most remarkable, launching into its subject as though interrupting Bach mid-phrase, unafraid to enter spaces of modernist dissonance, and rife with passages of fanciful ascension.

Although music was not taught as a discipline at the Bauhaus, there was great musical talent among its students and also the masters, and concerts were an integral part of social life. Wassily Kandinsky, who was a close friend of Schoenberg, likened painting to composing music and used musical terms to identify his works, as did Paul Klee, who was an accomplished violinist and often played duets with Feininger.

“Music is the language of my innermost self which stirs me like no other form of expression,” Feininger would later write.

related...

-

Master Builder

His compatriots made institutions of their music. William Schuman made institutions.

Read More

By Russell Platt -

Back to Bach

Pianist András Schiff revisits The Well-Tempered Clavier and other totems of J.S. Bach — on stage and on record.

Read More

By Bradley Bambarger -

Evolution of Form

Everything you always wanted to know about Baroque concertos (but were afraid to ask)

Read More

By David Hurwitz