by Daniel Felsenfeld

The British composer Benjamin Britten is well documented on disc and in print, frequently performed, lionized by many — especially those in the opera world — and often referred to as The Greatest British Composer Since Purcell (which either praises him or damns him with faint praise). But music history is most often taught as a recounted lineage of aesthetic successions, influence writ large, a slew of begettings and begats, epochal waxings and wanings, dawns and dusks, ideas giving way to other ideas, the churning of centuries in the service of progress. While a sequential narrative is a necessary contrivance for those who need to address totality— one has to start (and end) somewhere — it leaves little room for counterargument, for those working outside the metanarrative.

And so Benjamin Britten is left stranded outside the conversation.

Music history teaches that two schools of thought formed in the early-to-mid-twentieth-century. These schools rallied around the Apollonian and Dionysian poles of Igor Stravinsky and Arnold Schoenberg, respectively (though such ill-matched and ex post facto descriptives only somewhat suit these two nuanced and complicated composers), while a separate group orbited the distant planet of French experimentalist Erik Satie. To oversimplify, Stravinsky began with native folksong and waxed retro-classical, while Schoenberg, the German expressionist, created a system of composition with twelve tones that paved the way for ur-systemic composition of the highest order (although the algebra in the process could, to some, become the process). Satie, meanwhile, held that major triads — verboten for Schoenberg and freighted for Stravinsky — could be rash and experimental. In these absurdly reduced historical narratives there is simply no room for Britten, which means his broad influence is often conveniently omitted. But perhaps there are also other, more complex reasons for his omission.

Britten grew up middle class, which in the United Kingdom of the First World War meant quite a bit. Until that time, genius — real Mozart– or Beethoven–level genius — tended to originate from either the aristocracy or within bohemian squalor and burbling chamber pots. Britten had things easier than most. He so adored his childhood that he spent a lot of time pondering, through his music, how to return. He endured a customary, excellent/terrifying Dickensian education that taught him to “do a good day’s work” without undue fuss and to fear his superiors. When he made his move to London, he fell in with the usual bohemian circle of many an artist’s youth — his circle just chanced to include W.H. Auden. It is hard to imagine more opposite poles: Britten the deep still waters, Auden the effusive raconteur whose annoying gregariousness belied his capacity for nuanced thought and its passionate expression. Yet this dyad makes more than perfect sense: one can imagine the long, British discussions between them. At one point Auden offered succor to a young Britten about to play a piano concerto in public, assuring him it would be an aid to the seduction of a certain someone — who ended up being tenor Peter Pears, Britten’s lifelong companion and muse.

Auden managed to both sum up and further enshroud Britten in mystery with his 1938 poem “The Composer,” which ends:

Only your notes are pure contraption

Only your song is an absolute gift.

Pour out your presence, a delight cascading

The falls of the knee and the weirs of the spine,

Our climate of silence no doubt invading;

You alone, alone, imaginary song,

Are unable to say an existence is wrong,

And pour out your forgiveness like a wine.

There is no doubt to which composer Auden was referring. Britten, to him, had become music.

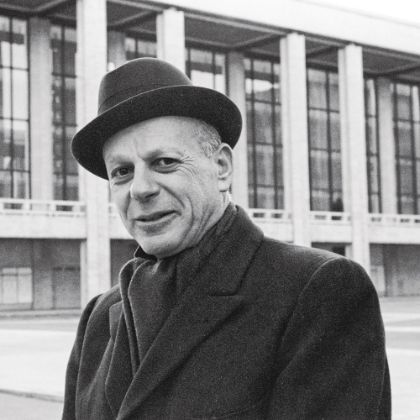

At work. Benjamin Britten at his studio in Crag House, Aldeburgh, England

Duo. Benjamin Britten with his lifelong companion and muse,

Peter Pears, in Brooklyn.Game-changer. Anthony Dean Griffey (center) in the title role of Britten’s Peter Grimes at the Metropolitan Opera

After brief stints in New York City and Long Island’s Amityville, Britten became an international celebrity. He wrote early works for the Boston Symphony, built (like Wagner, and like him only in this way) his own opera house, and enjoyed the company of a famously insular and complicated clique of people. He wrote operas for his own touring company as well as for the coronation of Elizabeth II. He arranged folk songs and wrote symphonies in homage to spring [see “For Winter’s Rains and Ruins Are Over,” page 38]; he wrote cello pieces for his friend Rostropovich and made a requiem mass from the poems of a trench poet and pacifist; he wrote a ballet based on gamelan music and made several “operas” for church based on parables and Noh theatre. His output is as wildly varied as anyone’s — as that of Mozart, Richard Strauss, or even Leonard Bernstein. His surface naiveté often belied his artistic stubbornness: he intentionally misread a commission from Japan in order to write the piece he wanted to write (Sinfonia da Requiem), and he based his grandest opera (Gloriana) — a commission to celebrate the coronation of Elizabeth II — on a scurrilous and less-than-popular book among the royals.

This précis of his career helps little in reasoning him out, however. His talent is not the question, as few since Mozart have demonstrated such effortless prolificacy, have come by their music so quickly and with such ease (Britten could write a full-length opera like A Midsummer Night’s Dream, soup to nuts, in one unrushed summer). In fact, Britten’s barely-precedented level of mastery made his better efforts seem the product of no effort whatsoever.

But mere fluency is a parlor game; the work produced has to say something essential. In Britten’s case it often says something not only essential but essentially British. Britten’s music is not only deeply British, but speaks to and of a certain type of essential Britishness. He does not rely exclusively on folk tunes, ballads, pastorales and music hall to make his mark, but neither does he shy away from them, borrowing from all of these genres, melding them into a music of his own specific design. It is little wonder that British novelist Wesley Stace placed the critic–narrator of his novel Charles Jessold Considered as a Murderer at the premiere of Britten’s first opera, Peter Grimes [see “Variations on a Theme by Gesualdo,” Listen Vol. 3, No. 3]. It was an epochal event in British music, the “rebirth of British opera,” says Stace, “and I wanted my fictional critic to experience the very moment of it” — strong words from a possibly biased fellow countryman, but true. Before Peter Grimes, no British composer since Purcell had written any enduring operas, and Britten’s tale of the potentially murderous outsider in a seaside fishing village — replete with church hymns and drinking songs — fit the bill.

Also essential to understanding and appreciating Britten is his way with words — not as a writer of prose (for he was less than gifted in this area, or at least fancied no side career as an essayist) — but as a setter of texts to music. Britten possessed the composer’s gift for finding the appropriate words to match his music (rather than the other way around), telling the stories he knew he could tell effectively. But more than that, he had a gift for rendering the words into music. “Sir Thomas Allen,” says Mohammed Fairouz, a young Arab-American composer whose work is in the same lineage as Britten’s, “introduced to me, while I was in my early teens and producing my first art songs, the immense and lasting contribution that Britten had made to English prosody. My compositional life never recovered from the early impressions of the Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings or Rejoice in the Lamb, a choral work. The correct beauty of his setting of text (think of ‘e-ve-ry creature’ at the opening of Rejoice in the Lamb) has influenced hundreds of my songs and those of generations of composers setting text in English.”

This, however, still fails to address the “how” of Britten, a topic vastly more complicated. It can be agreed (even by those who view him as retrogressive) that he was possessed of an ironclad musical technique and of the gift of being able to spin much out of little, to make a pithy little tune into a vast feast of a piece: listen to the opening moments of Peter Grimes, which oscillate between two simple motives but build the necessary dramatic tension; listen, as Fairouz suggests, to the Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings, which opens with a melody for solo natural horn that haunts the remainder of the piece; listen to The Turn of the Screw, Britten’s opera based on the Henry James novella, which is as deeply structured as any dodecaphonic Schoenberg work but is built — the whole opera — on a single theme that contains all twelve notes of the chromatic scale. Listen to Britten’s Third String Quartet: within the opening “kernel” you can hear the entire piece. The strict and unrelenting method and rigor to his work does not begin to scratch what makes these pieces so effective — that’s just the “contraption,” no matter how “pure.”

‘What makes Britten’s music great lies in plain sight, in the distilled essence of what makes Britten Britten: it is a music of conflicts from the pen of a man of conflicts.’

All music of any quality plays in and around the ineffable, taking aim at the sublime, but what makes Britten’s music great lies in plain sight, in the distilled essence of what makes Britten Britten: it is a music of conflicts, from the pen of a man of conflicts. His technical ability to make a massively scaled work out of the smallest and most nugatory material is what makes his music overwhelming, but his insight into all aspects of human nature, from light to dark, is what makes it last. When Wesley Stace heard Peter Grimes for the first time, he was not only “quite overwhelmed with the music,” but also “very impressed with its acute psychology.”

Perhaps Leonard Bernstein put it best in his gravelly voice-over at the beginning of Tony Palmer’s Britten documentary A Time there Was:

Ben Britten was a man at odds with the world. . . . It’s strange, because on the surface Britten’s music would seem to be decorative, positive, charming — and it is so much more than that. When you hear Britten’s music, if you really hear it, not just listen to it superficially, you become aware of something very dark — there are gears that are grinding and not quite meshing and they make a great pain. It was a difficult and lonely time. . . . Yes, he was a man at odds with the world.

Britten’s body of work is demure but terrifying, technically bulletproof but emotionally jarring, childlike but erotic. That chiaroscuro duality sets the twee against the profoundly dark, the easy and entertaining against the too horrible to contemplate. In Britten’s music the grace and fripperies of Mozart lie with Berg’s weltschmerz through Purcell’s baroque lens by way of the English countryside. He need not pluck one style of music and ask you to be impressed by its displacement; Britten’s music is itself a displaced style. So perhaps the world with which Britten was at odds was not merely the world at large — the world that was not keen on a pacifist or a homosexual, let alone an artist who was, maddeningly, both timely and ahistorical — but the world of perception, the black-and-white cultural conscience that believed in a single way to make one’s work. And yet, as history often bears out, in these dark cultural crevices and aesthetic oubliettes, truths are free to flourish, far from the maddening crowd. That is Britten’s gift to us, and in the approaching celebration of the year of our lord 2013, which would have been his centenary, we can thank him by listening.

…

Listening to Britten

We are fortunate that Benjamin Britten lived in the recorded age, because we have a whole legacy of documents (thanks to a contract with Decca) under his own baton, which is a little like having Homer reading the audio book of The Iliad. So when seeking a recording of anything Britten — the operas or, say, the War Requiem in particular — that is the ideal place to start. Beyond that, one especially moving recording of his orchestral work Four Sea Interludes (taken from Peter Grimes) is Leonard Bernstein’s rendering on his final concert on this earth, which gets much of it “wrong” but in the right way.

Another place to go for excellent recordings of the operas is the Chandos label, which, under the baton of Richard Hickox (who had a gift for all musical things British), offers some stunning recordings of lesser-known pieces like Death in Venice, Owen Wingrave and Billy Budd, not to mention orchestral pieces like the Piano Concerto or Cello Symphony and chamber music that includes his neglected four string quartets (expertly done by the Sorrel Quartet). One perusal of the Naxos catalog offers an overwhelming amount, including discs devoted to Britten’s songs, arrangements of folk songs, choral works, church canticles and much more.

Virgin Classics offers not only an excellent recent recording of The Turn of the Screw (with Ian Bostridge under the baton of Daniel Harding) but also a long-out-of-print recording of the ballet The Prince of the Pagodas conducted by Oliver Knuessen.

…

related...

-

Master Builder

His compatriots made institutions of their music. William Schuman made institutions.

Read More

By Russell Platt -

From Christemasse to Carole

The birth of Christmas in medieval England

Read More

By David Vernier -

The Next (Not-So-)Big Thing

New chamber orchestras are popping up all over America.

Read More

By Colin Eatock