Béla Fleck discusses the origins of his name and instrument, the return of one microphone, his banjo concerto, dealing with weakness, his writing process and artistic expression.

By Ben Finane

With the passing of Earl Scruggs in 2012, Béla Fleck assumed the title of most popular living banjoist. His musical road has wound through bluegrass, jazz, world and classical music. The fifty-three-year-old was commissioned to write a concerto for banjo and orchestra by the Nashville Symphony. A recording of the work will be released in August on Deutsche Grammophon.

I didn’t realize that you had such a classical name [Béla Anton Leoš Fleck].

Yeah, I do [laughs], I got stuck with them. Three serious classical names.

Béla for Bartók. Is the Anton for Dvořák or Webern?

Webern.

And then Leoš Janáček. Those were big shoes to fill. It sounds inevitable that you found your way —

It’s an unusual story, actually, because my parents split up when I was one year old and my father is the one who gave me all those names. This is one of those splits where the parents were completely out of contact. So I didn’t actually meet my father until I was in my forties.

Sounds like your dad knew he was pushing you in no uncertain terms toward music.

It was hard to fathom. It was one of those very strange [laughs] situations.

I thought, ‘Well, Béla just must have Hungarian roots.’

I have honorary Hungarian citizenship, simply because the Hungarian embassy was so disappointed that I wasn’t Hungarian, they made me one. Absolutely true.

So I don’t think a lot of people know that the banjo made its way to America via West African slaves. Can you take us through the history?

You just said it all. The slaves taken from West Africa included people that played instruments that were from the banjo-type tradition, or what we’d call the banjo now. I guess we’d call it some kind of lute or oud tradition. And Pete Seeger’s the guy who told me that the banjo, before Africa, probably came from Mesopotamia, down the Tigris–Euphrates River into Africa, at some point way, way back. And I don’t know how he knows, but I’m sure he does. I’m comfortable with him being an authority — or not. [Laughs.]

Pete Seeger, of course, was very much responsible for bringing folk music to the fore in this country.

He played a huge part, especially in the Northeast. I love this idea that I got from Pete Seeger that, as an American instrument, the banjo’s actually from Iraq.

That’s something to think about.

Sure. Let’s stick to Africa, but if we wanted to incite a few people, we could go that way. I’m not pushing for that. A lot of Gambians, West Africans came over, and in Gambia they say that slave traders took slaves that played the banjo because more people survived the trips if there was music on the boats. I don’t know. That could be folklore; it could be true. I have no idea. But they said that on the early trips a lot of people died, and the slave traders didn’t like drums, because drums could incite people and the Africans could communicate with each other through the drumming. But an instrument like the banjo, they said, was innocuous, lifted the spirit. I don’t know. I was told that in Gambia, but I’m not sure how they would know.

It’s heavy to consider that that was the banjo’s introduction to this country. I grew up in east Tennessee, so bluegrass is in my blood, and growing up it was always the received wisdom that these were tunes passed down from our Scotch-Irish tradition. But in fact it’s a revival movement of sorts, you might say ‘faux-traditional.’

Yes, bluegrass is. But if you think about traditional music in general, bluegrass is a small branch of a bigger tree. And it’s a more modern branch that was really built around the microphone, based on moving in and out of the microphone — that’s how it’s balanced. And it’s a small group. It’s not a community music where you have six or seven guitar players and five or six banjo players and eight or nine fiddle players all playing in a room together, like they do with Irish music. There’s one of each instrument, so it’s show music. It’s a showcasing of the tradition, and obviously it changed a lot when Earl Scruggs came into the mix.

Scruggs was a real game changer who brought the banjo into the light with a new and formidable picking technique.

Yeah, remember that they called him the Paganini of the banjo in The New York Times when he played Carnegie Hall with Flatt and Scruggs. [Lester Flatt, Scruggs’s duo partner, played guitar. —Ed.]

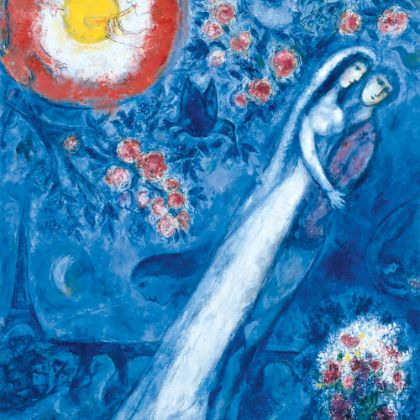

Pickin’ and grinnin’. Béla Fleck performs his Concerto for Banjo and Orchestra with the Cleveland Orchestra in Severance Hall.

Explain this technique of ‘moving in and out of the microphone.’

Well, one of the cool things about bluegrass in the early days — based on necessity — was the choreography. You didn’t have a lot of microphones for the whole band to play on; you had one microphone. And so the band had to move in and out of that microphone. And the good bands were beautiful at it. Flatt and Scruggs were a thing of beauty working that one microphone — and you heard everything perfectly. For Curly Seckler to have a mandolin solo, he’d have to go up to the microphone. If you were going to sing harmony, you needed to be just the right distance from the microphone, with the lead singer at just the right distance, too. Everybody would be at the perfect distance, and everybody would know how to get out of each other’s way.

You can still see remnants of that at those great venues in Nashville — I’m thinking of The Station Inn — where singers move back from the mic as they increase in volume, creating these haunting echo effects.

Yeah, it’s true! And in recent years, I would say the past twenty, the one-mic or very-few-mic approach has come back to bluegrass with a strong relevance. Whereas for many, many years everyone thought more is better. When everybody could have their own mic, everybody had their own mic. And they got monitors and everyone could hear themselves really well, and they just sort of stood in place, and bluegrass lost a beautiful thing about itself, which was the motion of it. Now it’s back — that’s a good thing.

So what’s great about classical music is there’s no mic at all. How’s that for a transition to get to your recently penned banjo concerto? There’s not a lot of precedent for this sort of piece. I think Pete Seeger did something in the sixties.

That’s right. There was a piece written for Pete Seeger, and he apparently wasn’t able to do it or wasn’t comfortable doing it and passed it along to Eric Weissberg, who played the piece. I’ve heard it: it’s an esoteric, artsy piece. I was asked to play it a few years ago and didn’t want to take it on, mostly because I wanted to do my own piece.

And your piece is not esoteric in the least — which I think brings us to the American vernacular. I’ve always seen Americans as outsiders to classical music, which to me remains a European tradition. But our advantage, what we bring to this music, is a comfort with importing and juxtaposing our own seemingly disparate sonorities.

I like that. I think about people like Gershwin, people outside of the classical music scene, writing classical works. Someone like that has a lot of appeal for me, being an outsider. In fact, my piece is now titled The Impostor. I think of it as if you’re trying to sneak this banjo into the orchestra and yet you believe you’re not who you are.... It’s the idea of sneaking into a masquerade without anyone knowing that you’re actually a gutter snipe. At the end of the piece, it comes out.

If the music communicates to people, it’s a success, and that other stuff actually doesn’t matter.

Certainly there’s some chromatic material at the beginning of the piece that gives way to more familiar bluegrass patterns in the finale.

Yeah, just at the very end, kind of like when the game is over. And you pull off your mask and it turns out you’re... a Montague! I kind of like that image. Even though nobody’s ever been rude to me or anything about being a banjo player, I can’t imagine that I’m not benefiting from everybody’s low expectations.

This is a through-composed piece with no room for improvisation or collaboration. How was that different from your normal process?

When you improvise, you’re going to play certain kinds of phrases that fall out of you very naturally, but when you compose, you have the time to come up with things you never would think of playing when you’re improvising. So I love improvising, but I do so much of it that I figured, ‘Well, why play in a classical situation and improvise? Why not try to learn as much as I can from the discipline of the situation?’ So I tried to write things that I never would have thought of, that I would have to compose and think hard on.

Do you think that discipline will find its way back when you return to your... non-classical music? I was trying to think of a word for what you play but I don’t want to say ‘bluegrass’ or ‘traditional’ —

Yeah, because I’m stuck in some sort of netherworld, no-man’s-land. Next week I’m playing duets with Chick Corea. Last month I was in India with Zakir Hussain. In between I was with Marcus Roberts, playing, basically, jazz.

So to answer your question: I’ve always thought of myself as a writer, whether it was for the Flecktones or tunes I’ve written to play with bluegrass bands. I’ve even won composition awards, but I realized that I had never actually written a piece from start to finish, every note of it. When I write, I tend to write a sketch, a melody and chord changes. Then I teach it to a band, a band full of improvisers, and we come up with arrangements together. And that’s not the same thing as writing every note for everybody. So I had to come up with my own bass line, my own harmony, rhythmic counterpoint, melodic counterpoint. While sections of this concerto could have been played by the Flecktones or other groups I’ve played with, the opportunity with the orchestra was to have eighty people playing and all these voices be carefully woven together.

I could take some of that thinking and bring it back to non-classical situations now, though it would be a pretty dirty trick to play on some of my friends. I’m not going to show up and tell Chick Corea, ‘Hey man, I’ve got fifteen pages of stuff I want you to play.’ He’s such a great improviser, I wouldn’t ask him to do that. But maybe on a certain piece, with the Flecktones or an acoustic group, I might do it.

Soon after writing this piece, I wrote a piece for banjo and string quartet [with Brooklyn Rider], about a twenty-five minute work, that makes up the second half of the album. I’m pleased with it, and there are things I learned writing the concerto that I was able to bring to this piece in terms of what I wanted to do better: a more relaxed approach, a little less desperation, more freedom and excitement. There’s some desperation in that concerto, being my first time through the composition process.

The Africa project. Béla Fleck performs with Malian singer Oumou Sangaré, with whom he recorded the album Throw Down Your Heart: Tales from the Acoustic Planet Vol. 3, Africa Sessions (Rounder).

Were there influences for you classically? I know you did the Perpetual Motion album [Sony Classical] in 2001. Are there classical composers that you like to return to?

Absolutely. I think to be a complete musician you have to have some kind of relationship with jazz and with traditional music and with classical music and with music from around the world. I don’t have an encyclopedic or studied classical knowledge, but I have a lot of familiarity. I grew up in New York; my stepfather played cello. I hung around with [bassist] Edgar Meyer, who helped me fall in love with Bach — again.

Edgar is a big influence on me: he’s the closest friend I have, he’s a great classical musician, he’s a top-tier player on his instrument in the classical world — with a healthy career outside that world. So watching him write pieces for bass and perform opened my mind to the idea that the banjo could do the same. And Edgar has a problem that there’s not a lot of repertoire for a bass player like him, ’cause no one’s expected to play the bass like that. So there’s no bass concerto by Bach. There are cello concertos. So Edgar is in a position where it’s ‘How do I play what I want to play?’ And he’s created a lot of the repertoire.

We wrote a couple of concertos together where Edgar was the leader and I was the collaborator. I learned how he did it, but I wasn’t capable of doing it that way because I don’t have the same grounding in theory. I also have a different personality. So I had to do it my way, which was sort of... dumb, you know

What do you mean by that? What was dumb about it?

What’s dumb about it is I don’t know what I’m doing, so my unconscious mind has to play a big role in the process — and that’s always been a big piece of how I work. It’s the strength and the weakness at play. I don’t really know classical harmony, but I’ve been around a lot of music and listened to a lot of it. So I write and I keep on writing until it sounds good to me, but I honestly don’t even read music. I’m just moving notes around on the computer screen until they sound good to me. And I’m not saying I don’t have some wherewithal, because I do, but my wherewithal is working with musicians one-on-one, or pulling good performances out of musicians or arranging for musicians in the room. My strengths are not in writing out, conceiving something on paper notation. I have to use my ear and react to things and rewrite, rewrite, rewrite. But eventually, I come up with something I like and it tends to hold some water because I’ve worked so hard on it that I’ve ironed out most of the flaws in my nature — with a lot of hard work and elbow grease.

I don’t think you’re alone there. We call that the trichord theory of composition: try this chord, try that chord....

Yeah! That’s what I do. I might start out with a little melody and write a bunch of counterparts to it, and then decide that the melody doesn’t work and write a new melody to the counterparts, and just keep on rewriting until it shapes up — and gradually it does. I tend to lose interest in things when there’s nothing left for me to do, and that’s when they’re done.

Perhaps not reading music really makes you get inside every note. Do you feel bad about it? Do you say, ‘Oh geez, I should really learn how to read music’? Or do you feel that ‘This is my method’?

I’ve had so many people tell me that I would benefit a lot from learning to play the piano, but it’s hard after playing the banjo for thirty-five years to go back to being a beginner and try and learn to read music so I can try and understand harmony and look at scores and understand them. What I have achieved is an understanding. While it will never be as solid as good learning would have been, it has given me some other things that I’m happy with. I’m a self-made man, for whatever it’s worth, with lots of flaws, but not like anybody else.

And it’s also supposed to be about artistic expression, and you can only express what you are. You can’t express what you were or what you would have been if you had gotten training. If the music communicates to people, then it’s a success, and the other stuff actually doesn’t matter — on a personal level. As far as looking at my concerto years later and comparing it to works by Bach, Beethoven and so forth, I’m not too concerned that that’s ever gonna happen. I’m more concerned that it’s an honest expression of myself as a musician and that I think it’s good and that I can get behind it and stand up there and that I would like to go out and play it over and over again. And I’ve enjoyed getting to play it again and again. I like the piece. That’s a selfish, weird thing to say, but if I didn’t, I’d have a real problem. Because I’m gonna be out there playing it and I’m a front-runner in the banjo world, so I want to do something that isn’t embarrassing for all of us. So I really put a year of hard labor into it — and it is what is.

...

Béla’s Best

1. The Telluride Sessions

(MCA) (1989)

Sam Bush, Jerry Douglas, Edgar Meyer and Mark O’Connor

2. Perpetual Motion

(Sony Classical) (2001)

Classical crossover

3. Live at the Quick

(2002)

Béla Fleck and the Flecktones et al

4. The Melody of Rhythm

(Koch) (2009)

Zakir Hussain, Edgar Meyer

Detroit Symphony Orchestra

Leonard Slatkin, conductor

5. Rocket Science

(2011)

Béla Fleck and the Flecktones

6. Tales from an Acoustic Planet

(Warner Brothers) (1995)

Solo project featuring Chick Corea, Sam Bush, Bruce Hornsby, Edgar Meyer, Branford Marsalis, Paul McCandless et al

related...

-

Respighi: Beyond Rome

Respighi’s set of variations is cast away for his more

Read More

‘Roman’ repertoire.

By David Hurwitz -

L’amico Fritz

Mascagni delivers beautiful music, libretto be damned.

Read More

By Robert Levine -

A Simple Love Story

It’s no accident that Puccini’s La bohème remains the most performed opera.

Read More

By Robert Levine