Hilary Hahn discusses diving in to new music, what it means to be American, giving her collaborators an online voice and her knee-knocking introduction to improvisation.

By Ben Finane

American violinist Hilary Hahn debuted with the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra at the age of twelve and signed a recording contract at sixteen. Now thirty-three, she has already recorded numerous albums of diverse repertoire. Her 2012 album, Silfra (Deutsche Grammophon), featured recorded improvisations made in collaboration with pianist Volker Bertelmann, known as Hauschka. Hahn’s project In 27 Pieces: the Hilary Hahn Encores is a collection of commissions for acoustic violin and piano, each no longer than five minutes and all performed with pianist Cory Smythe. You can follow Hahn’s violin case on Twitter: @violincase.

You’ve taken a bold step with In 27 Pieces: the Hilary Hahn Encores. This appears to be a jump off the high dive into the deep end of new music.

It is! [Laughs.] I didn’t think it was going to be, but it is. I had this idea of a commissioned encores project for quite a while, but didn’t know where to start. So I started with the music — which is what it’s about in the end. I did a lot of listening, geared toward composers who would be a good fit, but also who would be representative of what’s happening in contemporary music. I wanted it to be comprehensive but personal. So I tried to find composers who really spoke to me.

Why did you want to do this?

It just felt like a project I needed to do and that I needed to step up and make happen. I used the internet as many ways as I could. I wanted to make sure that composers had an online presence, so that if people liked the works that I had commissioned they could look into that composer’s work and buy a record, find out about concerts, support them in some way. The internet also has lists of composers in every kind of category you can imagine, and I went through as many as I could to learn about people I hadn’t been exposed to. Composers programmed in a classical concert are simply not going to represent all the people in classical music today.

Audiences are still having difficulty with contemporary music — which includes music by Schoenberg, Ligeti and others — that at this point is no longer contemporary! How do we convert them? Or is it necessary to convert them?

I don’t know. I think people are essentially going to like what they like, but I think they can connect to music they don’t think they like by just listening to performances of it. [Laughs.] That sounds overly simplistic, but you’re not going to like every performance of Mozart that you hear. Often, with more contemporary works that are performed less frequently, people hear one interpretation of it and that’s their frame of reference. And there’s a very good chance that what they’re not liking is the performance — and not the piece. Often these pieces aren’t as ingrained because they aren’t played as much, so you’re starting from further away than when you work on a piece by Brahms, for example, that has traditions — you almost know it before you look at the score! With a piece you don’t know, it takes some time. Often we don’t have a lot of time when preparing the performance, especially when it’s not chamber music. When it’s a larger group of people it’s just harder to get people together for enough rehearsals to internalize the piece the way we’ve internalized Classical and Romantic works. As an audience member, you may not have heard it before either, so you may not be listening for your favorite part — and hearing it the way you want to hear it. You’re hearing it how it’s presented to you, affected by how you’re listening that day, how people are playing it and whether you’re connecting with the performers, on a musical level or not. So I think just by giving it a few shots, by hearing different performers, or by listening to the same recording a few times before making a decision about it, you learn a lot about yourself as a listener — and about the music itself.

But ultimately, if someone’s not going to like it, that’s fine. It’s fine for people to give something a chance and then not enjoy it and decide it’s not something they’re going to pursue, because that actually opens up their listening time to other things they might discover. There’s a way that people, by listening, identify themselves and their own range of taste. It’s very personal. You can’t say that people should like this or that, regardless of how popular or how rarely played something is.

What did you learn from tackling Ives’ sonatas with Valentina Lisitsa, and did you find anything particularly American about his music that struck you?

Well, of course the tunes are very American; we recognize them as tied up with our history. I actually learned a lot about the structure of music by working on his stuff, and I don’t mean that in a dry way. It’s really hard to put Ives’ music together when you’re working on an ensemble piece. You’re taking it apart from day one, before you can even figure out what it’s saying. When you finally put it together, you figure out where things line up and what’s supposed to be where. Then it starts to speak, and once it does, it has so many things to say. Every performance is so different, because there are all these juxtapositions of melodies and harmonies and timings. And if you think about how any one of those things can be tweaked a little bit for any concert, there are an immeasurable number of tiny changes that can completely change the work in live performance: You just don’t know where it’s going to go in practice; you have to get onstage with it.

I think Ives managed to hit on a lot of elements in classical music that were important from his time forward, that have influenced people — whether through him or through some kind of zeitgeist or through new traditions that were being formed. I definitely feel that working on his music helped me get into a lot of the more contemporary music that I’m playing today — from a playing perspective, not an appreciating perspective; I would have appreciated it anyway. But knowing how to look at something, put it together and what to play around with onstage, I learned so much of that from Ives. And playing Ives developed out of everything else I learned until then, as well. It’s just part of a big continuum.

Would you agree that any piece of music you learn helps you categorically with music you’ve already learned?

Yeah, it seems backwards, doesn’t it? [Laughs.] It seems like it should only be going forward, but it does go back. I think everything that you learn, because you’re constantly revisiting things you’ve played before in a different time in your life or in a different context, it changes it when you come back to it. These things you learn you can apply back to things you learned before.

It’s André Topia’s theory of ‘contamination,’ where a new work ‘infects’ your reading or interpretation of a work you are already familiar with and puts it in a new perspective. I think that’s really cool.

I do, too. I think it’s a very positive process, and I think it can happen through any number of influences. But it is amazing how something just takes on a different tint all of a sudden! You never really saw something a certain way and then, ‘Oh wow, look at that color!’ [Laughs.] Or you remember something you tried in another piece and then recognize it in something you’ve been playing for a long time and that really gives it new life. It’s not that it is worse or better on one side of the realization or the other; it’s just different. It gives you a new way of trying to play the music, which can only be helpful in the long run.

‘I approach every piece with the same process and goal: to bring the music across to the audience in the best way I can connect with them.’

I asked Joshua Bell the same question I’m about to ask you. Do you feel that you’re saddled with an American identity when you approach a project?

No. I don’t know what it’s like to have any other identity. [Laughs.] I mean, maybe I am, but I just can’t see it. I think because I do so much traveling, I’ve always tried to fit in as best I can — not in a musical sense but just in a day-to-day sense. I don’t want to be the person who’s out in sneakers and a ponytail and lots of makeup and everyone else is wearing monochrome colors and knee boots. I like to observe my context and learn from what I see, because that’s inspiring to me and helps change my perspective. I try to blend in, visually and socially, to every country I go to, but it’s not easy. Primarily, I consider myself American; I’m really happy to be American. I love nature in America; it’s fantastic and beautiful and a great place to live and travel in. In my head I am American. People need to have a few identifiers to set other people apart; it’s part of language. You can’t talk about someone without describing them a little bit, and I find that nationality is a very easy way to describe someone, so it comes up a lot. But now that I’ve actually thought about it that way. I don’t feel that I’m saddled with any kind of identity; I feel that I’m free to explore whatever identity I want because classical music is so international.

And through this project, with all these composers, I’ve been seeing firsthand how individual people are with their creativity, and it’s really exciting. That’s a side I didn’t expect. I expected composers to have similar working processes. But they are so different from each other: where they get inspiration, why they write, what they learned and how they apply it, and what they enjoy about their work — it’s just all so different. And I feel that it’s such a global community that you pick and choose your identity these days — and that’s a great thing.

It seems clear to me that for you, the internet — the global village — is an important way to communicate your passion, your projects and your recommendations about classical music.

I really like having the opportunity to present my colleagues the way they are. That’s why I do the interviews [visit bit.ly/W75B1E]. People tend to say more in an interview than they do in a conversation. There’s a bit more explaining because you try to make sure that whoever might be observing the interview in the future has the same basic understanding, so you explain your perspective. When you’re working with someone, the assumption is you’re coming from the same place, so it really helps to hear these composers explain their ideas. When I was younger, I had a chance to meet people in arts administration and orchestra members, soloists, conductors, chamber musicians, and I got a feel for the music world. So what I try to do with the interviews is present as varied a picture of the music world as I encounter in the day-to-day. And it’s a fascinating place; there are a lot of really interesting people in it. And for anyone who appreciates creativity, I think the composer interviews can give a lot of new ideas and help people understand what it is to really make music from a blank page.

Everything I put online I look at as a resource. There’s no ulterior motive; it’s just there for whoever might be interested, whoever it might inspire or make a difference for.

You play works on both sides of the twentieth century. Do you approach a piece by Bach the same way you approach a piece by Charles Ives?

There are different ways to define even the word ‘approach,’ whether you’re talking about how you learn a piece, how you bring it across to an audience, or how you program it. Musically, I approach every piece with the same process and goal: to bring the music across to the audience in the best way I can connect with them. That’s an interpretive goal, so that the music speaks to me but it’s also speaking to the audience. You have a process that you go through, which is learning the piece, becoming familiar with the ensemble aspect of it, performing it, working with your colleagues. And every colleague has a different concept of the piece. So you reconcile their ideas with your ideas and come up with a mutual interpretation that’s exciting, fun to perform and flexible so that the spontaneity of the moment can come into the more general interpretation. From there, you just keep performing it and learning! So that’s the process for me with everything. In that sense, it is the same.

As far as programming, I always look for something to tie the pieces together that I’m playing. For something like Ives and Bach, I want to make sure that I set a context for the music that is a bit different from the context that people assume, but something that makes sense musically and sounds good back-to-back. I of course don’t try to play Bach the same way I play Ives. They’re different styles, so in that sense it’s a different approach.

Is what you take into account playing Bach different from that of Ives in terms of performance priorities?

Every composer is different, but every piece is different [Laughs], and every piece demands a different kind of attention to various details, and the proportion of those details is also distinctive — from one piece to the next and also within a composer’s works.

You’ve just spoken to the importance of coming up with a mutual interpretation when working with colleagues. This leads us to your Silfra album. With improvisation becoming a bit of a lost art in classical music, can you discuss the process for this album and, as a classical musician, the skills you drew on to collaborate and improvise?

We didn’t have a framework when we got to the studio, only the years we had worked behind closed doors playing together. And the improvisation — made from a combination of approaches — was ultimately what we wanted to try out. There was no pressure, and we didn’t tell anyone. [Laughs.]

It can be really nerve-racking when you have no experience performing without a script. Every time I’ve been in a new improvising situation, I’ve always been unsure of how it would go. But then the reason I find myself in these situations is because it’s the best way to achieve a result that I’m after.

The first time I found myself improvising, [singer-songwriter] Josh Ritter had invited me to be a guest at one of his performances. I thought I knew all the songs we were doing, and when I got backstage, he was singing them in a different key, so all the little violin parts I had written out didn’t work! [Laughs.] So I had maybe half an hour until we got onstage and just tried to ensure that I learned the chord sequences and stayed within them — and that was my first experience improvising.

That’s sweating bullets, because you’re thinking, scrambling on so many levels.

I know! I know! [Laughs.] I think my knees were knocking, but it was really fun. I had a great time, and it enabled me to perform music I wouldn’t generally perform, for a different audience. Ideally, if I’m working with someone, I want to enhance the performance, rather than distract or, um, ruin. [Laughs.] So that was my focus in my first improvisation experience: Don’t ruin his song. He was open-minded and fun and encouraging, and we wound up touring together later, and that was a shared-bill experience, so I continued to improvise on his songs.

Up until I started working with Hauschka, when I had done anything improvisatory, the piece had already been written and I was working my way around it. I wanted to know what it was like — this idea of something from nothing — to be part of the process where, if you were writing, you’re looking at a blank page. You can play anything: What do you play? That was a question I had never really been exposed to. Either the music was already written or the chords were already written. So I wanted to do something with Hauschka that was, from the beginning of the collaborative process, very creative — and creative from scratch.

related...

-

When the Shoe Fits

Prokofiev’s Cinderella is much more than a charming retelling of the beloved fairy tale.

Read More

By Thomas May -

Respighi: Beyond Rome

Respighi’s set of variations is cast away for his more

Read More

‘Roman’ repertoire.

By David Hurwitz -

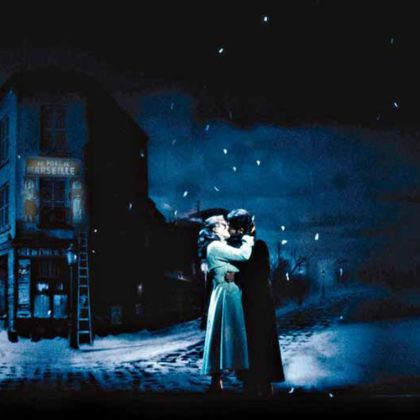

A Simple Love Story

It’s no accident that Puccini’s La bohème remains the most performed opera.

Read More

By Robert Levine