Joshua Bell defends his ventures and aesthetic.

By Ben Finane

Photographs by Dario Acosta

Virtuoso Joshua Bell is the most recognized American violinist today. Because of his profile, Bell has the Herculean burden of meeting the varied expectations of anyone and everyone. Over the past decade, he has suffered disappointment from many in the classical community for his oft-marketed image as a “crossover” artist. But those who would dismiss Bell have simply not been listening — either to his vast core-classical London/Decca discography of the nineties or to the gems to be unearthed within his Sony Classical catalog of the aughts, namely a bluegrass album with Edgar Meyer, a film score by Corigliano and tasteful vintage-style albums of encore pieces. His forthcoming project is a “French” album — Franck, Ravel, Saint-Saëns — with pianist Jeremy Denk.

Expectations and image have taken a visible toll on Bell. Sitting on the roof deck of his Gramercy apartment, any mention of a project that falls outside the core-classical sphere invariably elicits the reflexive response, “That’s two percent of what I do.” He is a little nervous, a little wary, a bit weary. Introducing himself, he mumbles his name, almost apologetically. Yet pushing resolutely through any defensiveness is a driving passion for — and conviction in — the music he champions.

You’re not afraid of crossing borders, of venturing away from classical, away from core classical, even away from classical altogether. Your Grove [Dictionary of Music and Musicians] entry says you’re ‘keen to escape the classical mould.’ Would you like to comment on that?

[Sighs in disgust.] When I hear that it makes me want to ask you, ‘What is classical?’ Because what does that mean? Classical is music spanning the last four hundred years, from Monteverdi to Stockhausen to music written today. I think in a lot of ways music is music, and classical means serious music? And what does that mean? How do you define what’s serious?

E-Musik and U-Musik [‘entertainment’ and ‘serious’ music].

Exactly, so I have a hard time with that. Some people might look at what I’ve done, at my repertoire, and say it’s ‘adventurous,’ I venture outside of classical. And then others might say it’s ‘conservative’ because I don’t do avant-garde, new classical, whatever that is.

Is it fair to say you’re a tonal guy?

Yeah. So for me, I do an arrangement of Porgy and Bess and people say, ‘Oh, he’s venturing outside of classical music.’ Or West Side Story. I find more in common with a Gershwin song and a Schubert song than with most modern music written today. And yet those two would be labeled classical, while playing a Bernstein thing or even a bluegrass tune, that would be somehow crossing over. But to me this is much more in line with how I was trained as a musician and how I view music. Or doing a film score, to me it’s all within the realm of how I was trained. Of course, there are projects where I’ve had to stretch — when I played with Edgar Meyer and Sam Bush [for Short Trip Home (Sony Classical)], immersed in playing with these guys —

— bluegrass pros —

— total pros, but [Bush] doesn’t really read music that much, so for him it was a stretch, too: he had to now read the music Meyer wrote and stretch a bit toward where I was coming from. So that was a situation where I wasn’t getting into the style as much as I could — I never for one second tried to be a bluegrass violinist, and Edgar didn’t want me to be: if he wanted a bluegrass violinist he would get a bluegrass violinist.

You weren’t playing the fiddler.

Right, he wanted to use my strengths as a classical violinist to play his music, which definitely had bluegrass roots and elements, but which he took to places with classical music technique. As classical musicians, we’re trained to wear many hats anyway, that’s what we do. In a single program, we’ll play Bach, then Schubert, then Prokofiev, and these are different approaches to phrasing — you really have to change gears. So getting inside a bluegrass style is not all that different to saying, ‘How do we approach Bach?’ You have to get inside a different way of phrasing, intonation, use of the bow.

When I play Baroque music, it’s always finding the balance to being authentic and being honest to one’s self and not feeling as though you’re copying a style. Music, as far as I’m concerned, always has to feel like you’re inventing it on the spot and has to feel completely natural. So when it comes to Baroque music, I allow my years of playing with musicians that might be more historically informed in their approach — Roger Norrington, John Eliot Gardiner, Steven Isserlis — to slowly change my approach to Baroque music, but I’ve never felt like I was just copying a style. You have to let it seep in. And I did the same thing with the bluegrass: it slowly started to feel idiomatic to play a certain way. And so I started to sound more like a fiddler, but I’m never going to be Mark O’Connor. And I didn’t want to be; I want to be me.

Are you espousing bluegrass and film as American idioms and therefore part of our classical tradition?

Well, movies are international, and bluegrass also came from Irish fiddle. And as far as being American, people like to label me as the American violinist, and yet, what does that mean? My teacher [Josef Gingold] came from Russia, and yet from the Belgian-French School of violin-playing — and he influenced me more than anyone. What some people call the American School would be Dorothy DeLay and Juilliard; I never went there and didn’t study with her. [Joshua Bell grew up on a farm in Bloomington, Indiana, and attended Indiana University — Ed.]. Half the people I play with are European. To what degree do I think of myself as an American? We live in such an international world now that I think those sorts of labels are not so applicable.

As classical musicians, we’re trained to wear many hats anyway.

Is it unfair to be saddled with an American identity every time you approach a project, as though you’re going to give an American spin on Bach?

Yes. I’ve heard some pretty lousy Mozart interpretations from people born in Vienna. [Laughs.] As far as I’m concerned, it’s not where you’re born. There’s this idea that people born in America should be able to play Gershwin and people born in Vienna should be able to play Mozart, and the location has only a small amount to contribute to that. Music is music and you either relate to it or you don’t. I won’t play music that doesn’t touch me, where every note means something to me and I can tell a story all the way through. It would be like someone repeating a joke they learned but doesn’t know why it’s funny: you’re never going to make anybody laugh. [Laughs.] And it’s the same with music. Some people will look at the Schoenberg Violin Concerto and just feel at home with it — and it could be location, it could be a personal thing, the music speaks to them. As of yet, Schoenberg, some of the twelve-tone Schoenberg things, very little of it speaks to me in the way that Schubert does or Gershwin does. I’ll keep giving it a try — I do want to expand my horizons in that department as well — but I’m very careful because you feel like an impostor if you feel like you don’t really believe one-hundred percent in the piece you’re playing.

‘Crossover’ has developed some tough pejorative connotations. But just taking Romance of the Violin [Sony Classical] as an example, this is a great album of transcriptions.

Thank you. What’s interesting is that people might view a crossover project such as that as though it’s something that’s never been done, as if it’s a new commercial phenomenon. In fact, it’s a throwback.

A Heifetz throwback.

Heifetz and earlier. Look at the nineteenth century, Sarasate and the great virtuosos of the time, they took operas — Faust, Carmen — look at Busoni, who took Bach and distorted it into his own crazy interpretation on the piano. The art of transcription was the way much of music was appreciated because we didn’t have recordings. Music was celebrated in this open platform sort of way, where you take what you want and make it yours. And there are people out there talking in terms of the original, authentic form in terms of the fundamentalist Bible. People may have spoken in terms of tasteful and less tasteful versions of works, but it was very accepted. For Kreisler, transcriptions were so much of what he did, and he even took on pop tunes. Heifetz, too, he did a duet with Bing Crosby, ‘White Christmas.’ Did anyone say, ‘Oh, you’re not a serious artist, Heifetz!’ And it ties in today, where we have this need to divide everything into, how did you term it earlier, E-Musik and U-Musik —

— entertainment music and serious music —

— and sometimes in Germany I get the feeling that that’s a standard breakdown and I think it’s a great disservice to a lot of great music — what I would call great music. This brings us back to the Romance album. Saint-Saëns, for instance, one of the great musical geniuses of the nineteenth century, wrote unique music, and is often relegated to being cheap music as compared to Brahms, who was alive at the same time. To compare them is unfair. While Saint-Saëns in some cases wrote profound music, he wasn’t trying to be Brahms. It’s like comparing one chef’s soufflé to another’s osso buco and saying, ‘Which one?’ They provide different things. That’s something that Gingold, my teacher, really instilled the value of for me: Saint-Saëns, Fritz Kreisler, Wieniawski — he treated this music with reverence, and when you listen to Gingold play a Wieniawski concerto you’d be convinced this is profound music because he treated it that way. And Kreisler as well. It’s elegant and serious music in its own way. If you treat it like a piece of crap and schmaltz it up, then it’s going to be what you think it is. I love transcriptions; I love them from a composing point of view. I’m a wannabe composer; I’ve always written my own cadenzas since I was a teenager.

Tell me a bit about those cadenzas.

I’ve always loved doing it. I’ve felt at my most creative when writing a cadenza for the Brahms Concerto or when I do my transcriptions. For instance, for this past album, At Home with Friends [(Sony Classical)], I sat down with Frankie Moreno, a pop-rock pianist and singer I ran into in Vegas, and we wrote a transcription of ‘Eleanor Rigby.’ It was a fun, musically challenging puzzle, taking the essence of ‘Eleanor Rigby’ and turning it into something more intricate, and you might say ‘more classical’ because of the added harmonic complexity.

I think the more unsuccessful crossover projects are those that contribute to the dumbing down of classical music. For me that’s this distasteful idea that we need to take a classical piece, even the Beethoven Fifth, and do this rock version and dumb it down. What interests me is the opposite.

What has drawn you to your film soundtrack projects?

Film soundtracks comprise about two percent of what I do — it’s just a side thing. It started with The Red Violin. I was always fascinated with film music, with how music is used in film. In my generation [sizes up his interviewer], in our generation, music has a great impact on the film. When they said they were making a movie about a violin with a heavy violin soundtrack, I jumped at the chance. It was a natural extension of what I do. And not once did the idea of ‘crossover’ even occur to me; it was just a musical project. Just a good experience — being involved with John Corigliano, my first time being on a movie set, I got to go to the Oscars, it won the Oscar — a great first experience.

Knocked it out of the park, right?

Now when is the next violin movie going to come out, and will they ask me to do it? Chances are, not in my lifetime, but that got me interested. Since then, perhaps because of that, I’ve been the go-to guy when they want a violin solo in a film. One that was interesting was Ladies in Lavender, not a big commercial success in this country but a very nice score. It’s certainly a valid thing to do. John Corigliano himself has only done a couple films. You might ask him that question: ‘Why are you doing film scores?’ He’ll do it if it’s something that’s artistically compelling. He did Altered States twenty years before he did another one with Red Violin. I don’t think anyone can fault him for doing something that’s not ‘serious.’

I’d say you’re also doing your best to bring classical music to a larger audience.

Well, that’s a secondary goal, I have to say, being a selfish artist. As an artist you first do things that are compelling from an artistic point of view. And you can drive yourself crazy worrying about how people are going to judge you for those decisions. So that’s primary. But certainly the secondary goal, when they make movies such as Amadeus, and to a lesser extent The Red Violin, those sorts of things are good advertisements for the power of classical music. When people saw Amadeus, millions went out and bought Mozart, because they were moved. It drives me crazy when people say, ‘I’m not a classical music fan because it’s boring,’ and they’ve probably been moved plenty without even realizing it, through films. One of the fun side effects of working with artists not in mainstream classical is they have their own fan base that has little overlap.

[Singer-songwriter] Josh Groban.

A good example. We did a concert where we shared the bill and that led to me doing a track on his album. There are probably some people in the classical world that would think that’s a bad decision for me to do something with someone who’s not a true classical — you know, how that somehow degrades anything else I do. I don’t understand [laughs]. Even from an ego point of view, I was on this album for half a track. There are movie stars who will only do films that feature them as the star and there are others who are big enough and have enough confidence to play a small role that seems fun to them without having to be the focus.

One of the benefits of that was to notice how many people I had coming backstage to my concerts after that project saying, ‘We had never heard of you before.’ [Laughs.] Not even ‘We had never heard your music’ — ‘Never heard of you! But we heard the track on Josh Groban’s album and got interested in the other things you’re doing’ and then they’re handing me a CD of the Beethoven Concerto to sign.

So it wasn’t conscious, but I’m aware that this kind of collaboration can have that side effect, and it’s very rewarding to see people like that, not just classical connoisseurs, coming to the concert. When I play and it’s sold out and people are clapping between movements, where some in the audience might be shushing everyone and be offended that people are there who don’t know what they’re doing, I’m actually — ninety-nine percent of the time, unless they’re ruining the end of a slow thing too early — I’m gratified because that’s telling me that I’m reaching that audience beyond the core connoisseur.

Getting back to your question of ‘What is classical?’ and how we handle the term of ‘crossover’ —

And which kinds of crossover are acceptable. Like, somehow tango has become acceptable crossover.

Because of Piazzola?

Right.

I won’t play music that doesn’t touch me, where every note means something to me and I can tell a story all the way through.

It’s okay because it’s so regimented, we’re not having too good of a time.

I’m hoping that some of those boundaries — there are Europeans doing tango and things like that — I hope it becomes more acceptable. With me, ninety-five percent of what I do is core classical. So when people say, ‘Oh, he’s the guy who does — ’ and they try and put me in that box, it’s a small portion.

They haven’t seen your touring schedule.

True. Criticism from.... It’s very easy to get depressed about what people say, especially with the modern —

Do you get depressed about what people say?

Sometimes.

Why?

Because I’m human, I’m sensitive. Especially with social media and YouTube, people have no respect anymore. I find it really disturbing the lack of respect that people have on the internet for anybody. I’ve gone on to YouTube and they’ll have a Fritz Kreisler record and there will be people slamming him for being disgustingly old-fashioned and slurpy — and totally not getting the beauty, that he was one of the great violinists that ever lived. You can see that across the board. And the idea of comparing — people will go online and say, ‘This sucks; I like this version’ — and not realizing that first of all, you can appreciate both versions for different reasons. It becomes a contest: ‘This person sucks because I like this person.’

I don’t look at my own clips with people’s comments anymore because it’s kind of disturbing. The other day when Eugene Fodor died [1950–2011] — he was someone who as a kid showed great promise which didn’t.... He had personal problems. So in paying homage to him I went to see what was out there on YouTube and found a video of him and was just pleasantly watching something of his — I could have my own criticisms of Fodor, and people used to criticize him like crazy for being a showman and all this stuff — but there I am reading on the screen and someone writes, ‘Joshua Bell, if you’re reading this now, this is the way to play the violin!’ Like, why did they feel the need to insult — they actually said that! ‘Joshua Bell, if you’re reading this right now, this is the way a violinist should play.’

It’s a little surreal.

Why did you feel the need to insult me [laughs incredulously] on Fodor’s page?

I think, too, if I’m watching a YouTube clip, I can hide behind the anonymity —

— yeah, totally —

— of my screen name. So I can say, ‘This is terrible!’ without having to engage in a dialogue with someone. Maybe that’s part of it.

And unfortunately, a lot of this comes from students who are quite young. And it saddens me to see that kind of cynicism from —

— people who haven’t done their homework.

Haven’t done their homework, haven’t lived. When I was a kid we revered every single Milstein, Heifetz, every one of them — they were heroes. We didn’t say, ‘Milstein sucks ’cause Heifetz is better!’ We bowed down to them and revered them. Nowadays you get these young high school and college students that are already cynical about so many things and it makes me a little bit sad. [Pauses.] On the other hand, the technology is fantastic because we have access to all this stuff; I’m happy YouTube exists, I just wish people would have more respect for those who are out there giving their best. You may like one version more than another, but there’s no need to insult people.

related...

-

Respighi: Beyond Rome

Respighi’s set of variations is cast away for his more

Read More

‘Roman’ repertoire.

By David Hurwitz -

L’amico Fritz

Mascagni delivers beautiful music, libretto be damned.

Read More

By Robert Levine -

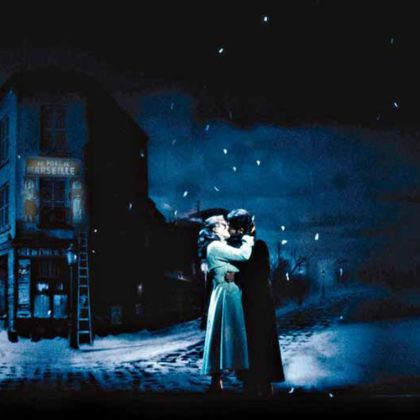

A Simple Love Story

It’s no accident that Puccini’s La bohème remains the most performed opera.

Read More

By Robert Levine