Rosanne Cash talks community, geography, learning on the road, reinvestigating the South, borrowing, melancholy, and respect for tradition.

By Ben Finane

Singer–songwriter Rosanne Cash, born in Memphis, Tennessee, is the daughter of the singer–songwriter Johnny Cash and Vivian Liberto. She toured with her father after graduating high school in the early seventies and earned a contract with Columbia Records in Nashville in 1980. She scored a number-one hit with the title track from her album Seven Year Ache (1981). More recently, Cash released Black Cadillac (2006), an album that marked the passing of her father, mother, and stepmother, June Carter Cash. In 2009, came the album The List, based on a list of a hundred country songs her father gave to her at the age of eighteen. Most recently, Cash released The River & the Thread — a collaboration with her partner, producer, and co-writer John Leventhal, and exploration of the American South — which won a Grammy for Best Americana Album.

I was born in San Francisco but grew up in east Tennessee. Recently, I went back to Tennessee to attend a funeral of a friend from high school, who passed away from cancer. At the funeral, his family played film footage from his wedding day of him and his mother and sister clogging — his mother had a tremendous influence on modern clogging — to Dolly Parton singing “Rocky Top.” His mother and sister then performed the same routine to the same music live at his funeral. It was wonderful — and such an ache, a cathartic moment that reaffirmed that, ‘Oh yes, these are my people.’

Those are the kinds of traditions that we cling to. That sense of community, it’s everything, isn’t it? It’s really powerful: it connects you to the earth.

I didn’t feel rejected, despite having been away for so long.

I just had a similar experience. Southerners are like that, even if you only have a peripheral kind of connection [laughs]. If you’re born in the South, or if your ancestors are born in the South, they embrace you. It’s really true, they have a very strongly felt sense of tradition and community — sometimes to the point of the detriment, that exclusion thing.

Yeah, I was never a member of the Good Ol’ Boy Network — and I knew it. The whole: ‘Just head on down and see Bill at the law firm and he’ll set you up with a job.’

[Laughs.] ‘Just turn left where the motel signs used to be.’

‘You’re gonna come to a road…. Keep goin.’ ’

[Laughs.] I love that. One of the greatest ones was my dad had a houseman — very Old South — and a snake once got into the house. The house was on a lake, ground floor. And my dad said, ‘Well, what kind of snake was it, sonny?’ The houseman replied, ‘Oh, it was just one of them house snakes.’ [Laughs.]

When I hear you speak, I hear Southern California, I hear that cadence —

Yeah, oh God!

You were born in Memphis and grew up in Southern California; you live in New York City. How do these geographies contribute to your musical identity? I see New York as a hip-hop town, Los Angeles as rock ‘n’ roll —

I don’t see it that way at all. Geography is hugely important to me and geography has resonance based on particular cities, more so in the past, unfortunately; there has been this sort of leveling of culture with the internet and McDonald’s. But distinctive personalities really interest me. Memphis is very different from Omaha. And I do not see New York as a hip-hop town at all, I see it as like the early folk scene in the Village, which contributed so much to my identity. It has everything from rock to opera. The breadth of musical curb culture here is staggering. And there is equanimity about it. I mean, Nashville really identified with country. LA really identified with rock ‘n’ roll, you’re probably right.

Nashville is a little less country now, though, isn’t it?

It is! The alternative music scene, my soon to be son-in-law — he and my daughter are getting married July Fourth — she lives in Nashville and he is in a punk band and they are really, you know, hardcore... and embraced!

As a singer–songwriter you don’t fit into that Nashville mold because you’re a one-woman show, in that regard.

Yeah, I think you’re right. Even when I was in Nashville, I guess I was there for about a decade, there weren’t that many women songwriters. I mean there were the old-school ones —

That’s a Good Ol’ Boy Network in its own right, isn’t it?

Oh my God, it still is. There was Loretta [Lynn], who was an anomaly, and then there were newer people like Matraca Berg. Then Mary Chapin Carpenter, but we were anomalies. I mean you look at the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame, out of how many dozens of men, there may only be about eight women?

Is that something that is shifting?

I don’t know. I mean Taylor Swift was a big shift, but you can’t really consider her country, can you?

No, more ‘pop country,’ that egregious category that has people from Canada faking twangs — it’s not authentic.

I agree, but there’s plenty of that in pop music, too, the pandering to radio.

When you were on the road early on, what did you learn from your father and from The Carter Family?

From The Carter Family — because we were in the dressing room so often when my dad was on stage — I learned how to play the guitar. Really basic things: they taught me how to play. The first chord I ever learned was from Helen Carter. They taught me all The Carter Family songs. Carl Perkins was in the dressing room, and he taught me a couple things on the guitar, but he didn’t have much patience for an eighteen-year-old neophyte. Also, from the Carters, I learned this naturalness about being on stage. June could be having a conversation with you and walk on stage without ever breaking stride. She was herself.

There was no persona that she had to put on.

The persona was also in the living room though, which sometimes would annoy you to death. She was the same on and off stage.

Was it effusive?

Yes, and bubbly and very Southern — with a lot of attention drawn to her. She was so charming. Her sisters, Helen and Anita, and her mother, Maybelle, were also exactly the same on and off, but they had more subdued personalities.

My dad was different. He was incredibly charismatic offstage, but internal and reflective and kind of quiet. Onstage, all of this power was focused in him, which is not something that you can learn. That’s something in the realm of mystery. But what I did learn from him was respect for your audience and a work ethic that was unwavering. ‘Respect for your audience,’ meaning he showed up for every performance — present. He never phoned it in and he never forgot what town he was in. He went on stage knowing that this was their hometown and that they were proud of it. And these people have a particular personality and their hometown has a lot to do with it. And ‘I know where I am and I came to perform for them, and they came to see me and it was their hard-earned money and they paid to come see me.’ That was always part of his performance, part of his persona, ritual, personality. One time I was out with him on the road, I was nineteen years old, and didn’t remember what town I was in. And I said it onstage, like, ‘Where are we?’ or something like that, and when I got off it was one of the few times he got pissed at me. He said: ‘Never forget what town you are in.’

Does just the act of performing live help you gather that inner strength or is it that you either have it or don’t?

I learned it to some extent. I sing to the far corners.

Back of the house?

Back of the house to try to include everybody. I know a lot of performers who do it right here [indicating in front of her].

If you’re not in the first three rows, forget it.

Forget it, or even if you are not on the stage! Like it’s all about them and the microphone. I always thought that was a selfish way to perform — even if they were shy. You have to include everybody and at least make an attempt at molding group energy. Seeing who they are in the first couple of songs and then feeling it out.

Do you adjust your set to the crowd?

Not until the end. At the end, if it’s been an internal crowd — you can tell they are really listening but are not giving you a lot back — then I might close with something that’s more aggressive, and if they need to be calmed down before I send them off into the night [laughing]....

A little denouement....

Exactly. The rest of the set I sometimes change three quarters of the way through, but the first part, not usually.

Let’s talk about what I’ll call your reinvestigation of the South. What musical discoveries did you make that were unexpected?

That is a good way to put it, by the way. We started the tour for The River & the Thread in Little Rock, Arkansas, with a showcase right before the record came out. We ended the tour a year and a half later, in June, at Dockery Farms in Mississippi, which was one of the great old cotton plantations in the South. Charlie Patton worked there and Howlin’ Wolf and Pops Staples and all of those blues musicians, who were around in Cleveland and Indianola and Greenwood; they had all passed through and there was a juke joint and they sat on the porch — it was straight out of history! And the Dockery Farms Foundation was formed. And we performed there. The concert was haunting. It was so powerful. There was some quality that was mysterious about it. Maybe we were all bringing that to it or maybe it still has the resonance of what had once happened there.

A lot of energy expended there over the years — in many ways.

Exactly. So at the after-party there was an old blues musician by the name of Cadillac John Nolden playing blues harp [harmonica]. So I kept cutting my eyes over to him at this party and nobody was paying much attention except the musicians, who would go over and really take in what he was doing. But I was talking to people and I didn’t have much time to talk to him. After the party, while everyone is leaving, the music stops and I go up and sit next to him and talk to him and he says, ‘You know, in the Fifties, when I was plowing the field behind my mule, we’d hear your daddy come on the radio at the house’ — I’m going to cry telling you this — ‘and we would run out of the fields and gather around the radio to hear your daddy’s voice.’ This man was eighty-eight years old. So he was there when Robert Johnson was there.

He was plowing in the Fifties?

Oh, even into the Sixties! I was just chilled to the bone and so moved. So I started talking to him more and started finding out a little about his life. He never became famous, but he had played the blues guitar. Then his wife left him and he was so broken-hearted; he took up the blues harp. So I went into the house after talking to him, I had someone take a picture with him. He was so full of love and you could still tell that he had this slight deferential quality to me. Like old black men would have to white women.

Well, still today in Savannah — or in Charleston, where I was at the Spoleto Festival, it was so beautiful but so very white-glove and lemonade. It wasn’t the South that I grew up in, and I encountered black guys who said: ‘Hello, Suh, welcome to Charleston,’ And I thought, ‘Oh Lord, they still make you, brother?’

I know. What kills me is that there is no bitterness, yet there so easily could be. And he was like that, Cadillac John was, so full of love, yet he, at the age of eighty-eight, was treating me with respect. It hit me — it should have hit me sooner, but it really hit me that I got three Grammies and all of this attention for this record that I had borrowed from his tradition.

Life with music & culture. (Clockwise from top left:) Doc Watson (right) performs with his son, Merle Watson, at the New York Folk Festival in July 1965 in New York City; The Dockery Farms Seed House, part of the old Dockery Farms plantation; Edward Hopper’s New York Movie (1939) was featured in the Melancholie exhibition; William Faulkner wrote the plot outline to his Pulitzer Prize–winning novel A Fable (1955) on the wall of his home in Oxford, Mississippi.

You are not the first borrower.

I know, but he had been there at the inception, and he never became famous. And I went into the house and burst into tears, I couldn’t stop crying for hours. I spent the next few days thinking about him and everything that he represented and what it had given me. Not only the music, but also what my grandparents’ lives were like — and also my fathers’ lives. It was his life. It was Cadillac John’s life. Plowing in the field, by hand, no electricity, giving birth at home — it was so profound to me! The beginning of that tour, Little Rock, at this rock nightclub — because Oxford American sponsored it because I had written a long story for their December issue — all fancy and then ending with that, it was an enormous lesson! And you know what? It was a lesson about race, too. My grandfather was a racist. No one has ever really come out and said that, but he was. And that chain was broken with my father — once he went away from that part of the South into the world.

That’s the whole thing, isn’t it? If you are in your little bubble, you just don’t know.

It’s very hard. And then the chain was broken with my father and me but has [further] transformed in my son and my children. My son doesn’t have an intolerant cell in his body. He is sixteen, he gave me this whole spiel about race, about how even if you are not racist there is some unconscious racism in white people because the world is set up for us and blah blah blah. I told him he was right! But I was thinking that if you go two generations back....

It’s hopeful. All these kinds of music come from black music. From blues, gospel —

Southern gospel, slave songs.

Bluegrass, too —

A white tradition actually, but with an African banjo!

Do all these threads sort of wind together, the relationship between all that music?

I think so. The British Isles and Africa, right? That is the genesis of all of it. The Appalachian songs that you can trace back to the Elizabethan songs and then the blues that you can trace back to work songs and Southern gospel and African banjo. Slave songs. Pain, suffering, all of those Appalachian songs about death and loss and never seeing your home again and war.

And they cut across the color line, those Appalachian tunes.

Well, the subject matter, the richness of it. It’s not all about hook-ups and break-ups. [Laughs.]

Sure, there’s that side genre of… pick-up truck, killed my dog, left my woman.

[Laughs.] That’s all of those topics reduced to the lowest common denominator. ‘I was drunk the day my momma got out of prison.’ Do you know that song? David Allan Coe? [“You Never Even Called Me By My Name.”]

You’ve spoken before about the Faulknerian South. Are we talking The Sound and the Fury or more Absalom, Absalom!?

You’d have to ask [my husband] John [Leventhal], he’s the Faulkner expert — in fact, that was his college thesis.

I imagine you are referencing the gothic feel and the characters.

Yes, of course. But the insularity, too. The gothic feel, the race relations. And also the great Shakespearian literary qualities, even in its simplest form, the blues. They say that there are five stories in twelve notes? I think the deepest stories and the deepest twelve notes are in this music. We went to Faulkner’s house and he has a novel written across the wall, the beginning of a novel that he wrote [A Fable (1955), for which Faulkner won the Pulitzer Prize] is on his wall: it’s still there. I like that idea, the metaphor of being so immersed in the mystery of your work and how it consumes you and the geography of it and the tangible quality of it.

You have also touched on the need to get out of your own way when you are performing. Can you unpack that a little bit? Is that distancing yourself from your ego? Just serving the music?

That sounds very grand, but it’s more difficult than that. I think the greatest performers do that. There is an element of real service about it, and then it goes beyond service to actually managing group energy, like Springsteen does — he can manage a stadium of people and manipulate them, in the best sense of the word ‘manipulate.’ I think the rest of us attempt to surrender, and at the same time, use our best skills. Linda Ronstadt had this great line: ‘You have to refine your skills so you can support your instincts.’ I think as a performer, it’s the same thing. If you have put in your Malcolm Gladwell ten-thousand hours —

— which I’m sure you have —

At this point, I have — if you’ve put them in and actually paid attention and really shown up, then maybe those skills will start to serve you in getting out of your own way.

I was listening to your [cover of Bob Dylan’s] ‘Girl from the North Country.’ It reminded me of Dylan’s liner notes to The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan: ‘What’s depressing today is that many young singers are trying to get inside the blues, forgetting that those older singers used them to get outside their troubles.’

Oh yeah, I’ve heard that. Dylan also said, and I’m paraphrasing: ‘The audience doesn’t come to hear your feelings. They come for their own.’

That’s a real wake-up call.

It is a wake-up call, out of narcissism. Director Peter Brook talks about self-consciousness and surrender, and if you’re watching yourself, it kills any chance of inspiration or mystery. Regarding ‘your feelings,’ I went to see this exhibit in Paris called Melancholie.

I saw that too — in Berlin!

You did?

It made me feel better about having an artistic temperament.

Me, too.

It made me feel okay about going through periods of... anyway, sorry, this isn’t about me.

No, you’ve exactly nailed it — it was a relief! The friend I was with, who is not really an artist, found it to be incredibly depressing and wanted to get out of there. But really, everyone from [Hieronymus] Bosch to Arvo Pärt: they took their madness and their grief and their despair and actually put it on a canvas or in music or in sculpture. And that’s what we are supposed to do — instead of medicating it. [Laughs.] I went to see it when I had just finished making Black Cadillac and I felt a little insecure because the album was raw and very dark. When I went to see Melancholie, I thought, ‘Oh my God, this is what I have done, I have done this too.’

When I was making Black Cadillac, I felt bad for my siblings that they didn’t make music and write songs, like this is going to save me and heal me.

But now that thread continues with your children.

My daughter isn’t doing it so much, but my son is. He just made an album at the age of sixteen, all his own songs.

The List. What are some songs on your list that you would want to pass down to your children?

Some dovetailing with my dad’s list: “Long Black Veil” would be on my list. And “Heartaches.” Some of the others on his list: “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry.” But I’d have to go into my Dylan and my Neil Young and my Elton: “Mona Lisas and Mad Hatters.” That for me is a perfect song.

Elton John also knows how to earn that money note. Delay, delay, delay —

— and then just kill you! The Beatles, “Here There and Everywhere,” and “No Reply.” Neil Young…. I’m thinking of a million of them, but do I want to say “Cowgirl in the Sand”?

What about Joni [Mitchell]?

Just about all of Blue is hugely important; that was a real awakening for me — and that’s not typical just to me; every woman songwriter of my age had that epiphany: women could do this.

In the Nineties, we had the grunge and the darkness — it was all irony all the time. I feel now, with the Millennials, maybe even with Gen Y, we have all these ‘indie’ bands that are rock but with an acoustic feel, with acoustic guitar and banjo, et cetera, I would call it the New Sincerity. There is no irony. And I feel that bluegrass, more than anything, has contributed to that.

Interesting, like the Carolina Chocolate Drops. And yet Rhiannon [Giddens] is also classically trained.

There you go. You have Bon Iver —

Love Bon Iver.

Heart-on-the sleeve type stuff —

Justin Currie.

It just wouldn’t have been possible in the Nineties or without the influence of bluegrass. Even a murder ballad, it’s not ironic. Doc Watson, pitiless —

I love Doc Watson. When I was in my late teens I spent a couple years in Nashville living with my dad, and Doc and Merle [Watson] played at the Exit Inn for five nights, two shows a night, and I went to every show.

So sometimes I’m slightly suspicious of the New Sincerity, as you call it, in certain bands. But it is heartening, and with [the soul septet] St. Paul and the Broken Bones [who performed as part of Cash’s 2015–16 Carnegie Hall series], there is no irony, there is so much respect. That’s what I love.

Respect insofar as a respect for the tradition they’re coming out of?

Yeah. I don’t respect artists who don’t know the tradition they’re in, who think they’re all new and all original. Nobody is all original! You are borrowing, and you better do it well and you better do it with respect!

related...

-

When the Shoe Fits

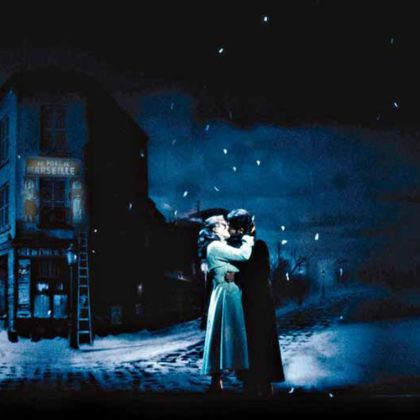

Prokofiev’s Cinderella is much more than a charming retelling of the beloved fairy tale.

Read More

By Thomas May -

Respighi: Beyond Rome

Respighi’s set of variations is cast away for his more

Read More

‘Roman’ repertoire.

By David Hurwitz -

A Simple Love Story

It’s no accident that Puccini’s La bohème remains the most performed opera.

Read More

By Robert Levine