Baritone Thomas Hampson sings America's praises.

By Ben Finane

Illustration by Demetrios Psillos

Following in the legacy of great American baritones, Thomas Hampson is equally at home in the opera house and in recital. His roles run from Mozart’s Don Giovanni to Busoni’s Dr. Faustus. He is a frequent interpreter of the Lieder of Schumann, Schubert and Mahler and a consummate scholar and teacher. This year, Hampson continues his Song of America project, a recital tour in collaboration with the Library of Congress that celebrates the 250th anniversary of the first published American art song. Hampson was appointed the New York Philharmonic’s first artist in residence. He spoke to Listen over Skype from Germany.

Looking at your Song of America project, where does American art song draw from classical tradition and where does it stand apart?

American song is as wide and deep and myriad as American culture can be. I have hung this year on the 250-year anniversary of the first art song in America by Francis Hopkinson, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, who sent violin pieces and songs to George Washington and said [apparently in a powdered-wig colonial accent à la The Rocky and Bullwinkle Show], ‘I believe this is the first American thing on American soil.’ And George said, ‘You’re probably right. I’m a little busy here on the Potomac, but I’ll take your word for it because I don’t have an ear for these things.’

Anyway, Hopkinson wrote some nice songs, but my thrust to American song is to be very respectful to the specific genre that is poetry set to music. I have always felt that when we look at song, especially ‘art song,’ or our version of Lieder, we see that we have always been preoccupied to find the best of our composers, the best of the epics and that sort of thing, and I think that’s slightly wrong-headed when looking at American culture. Because if you look at any particular timeframe in American culture and the cross-generational dialogue between, say, an early poet set by a later composer, you find that the creative spirit, this song-writing, this poetry set to music becomes kind of a marker or diary of our culture — America, which is very complex and born of so many different racial and cultural influences in and of itself, becoming America. And that’s the narration or the storyline that fascinates me and that this project is born of. It’s essentially saying what was it like to be alive at any particular juncture in our country, calling yourself American — whether you are French, German, Dutch, Italian, Chinese, whatever — regardless of that dialogue, what was it like to be alive and an American?

So in terms of the classical tradition, I guess the specific answer is certainly we’ve had ‘classical composers’ — however contemporary in whatever time they lived — setting folk music or arrangements of folk music, but we’ve also had an awful lot of people simply taking a poem, trying to identify that poem in that context of psychology, if you will, and framing it in a musical language that either augments the experience of that poem or articulates the very substance of what that poem is. I believe poetry and music to be very much two languages in a dialogue with one another.

And you see that dialogue continuing into present day?

Oh, without question! American song, the American dialogue between poet and composer is as active today as it ever has been. We have some brilliant composers — and I’m not talking about lyrics. I’m trying to make a distinction, because I mean, American song, what the hell is American song? What about the Lomax Archives? What about Carl Sandburg? What about Bruce Springsteen? And that’s valid, that’s terrific, but I’m talking about poems set to music. Of course you can list any number of — Corigliano, Mark Adamo, Richard Danielpour, Ricky Ian Gordon, Ben Moore — you could go through a whole list of very active songwriters, and they’re classical composers writing songs. They’re not setting a lot of folk song arrangements, which I would like to encourage them to do, but they’re writing a lot of songs. American song is blooming like crazy.

Fifteen years ago or twenty years ago, when academia finally got off the back of composers and allowed them to start writing melodies again and polyrhythms, it became a very exciting music. And I think people said, ‘Terrific!’ And we’re starting to rediscover composers like Samuel Barber or John Duke, who I consider to be two of the great masters of American music and American song.

When you speak about academia ‘getting off the back of composers,’ you’re referring to the return of tonality as an accepted practice?

Sure, but also the fun thing in American contemporary music, it seems to me, is the notion that the parallel existence of tonality and non-tonality is now completely acceptable — and useful and interesting and expressive. And the public is starting to come along as well — for me, this is a very positive development. And of course the profusion of polyrhythmic notation or genres, accentuated by various other cultures along with our own birth into jazz — quite frankly a lot of the jazz world is the cutting edge of the classical world, if you ask me. But that’s another conversation.

Do you find this to be a uniquely American phenomenon, this blending of genre and importation of other music?

I don’t know if I want to be that xenophobic — or let’s say chauvinistic. Certainly we can be very proud of the fact that in the American classical tradition, and especially the avant-garde tradition at the moment, we are doing that. We are doing it unabashedly and we are gaining audience and gaining listeners and opening people’s ears and so forth.... The answer to your question is ‘yes’, but the answer needs to be put in a context that encourages other cultures or other paradigms to start restructuring their walls. Yes, in Germany it’s getting somewhat better, but there is still this huge distinction there between E–Musik and U–Musik, meaning ernste Musik, ‘serious music,’ and unterhaltung Musik, ‘entertainment music.’ There is certainly cross-mixing, but there always seems to be this knee-jerk need to say, ‘Oh, well, even though that’s very serious, it has entertaining values to it,’ or ‘Gee, that’s so entertaining, but it has such a serious side to it, it could be a yada yada.’ In America — and rightfully so, it’s the way we’ve always been — we cover that ground quicker and we don’t spend a lot of time justifying one way or the other. We’re getting more to what Leonard Bernstein used to call the ‘good music and bad music’ mentality, which I think is a very good place to go.

Bernstein and Ellington, too, I guess [‘If it sounds good, it is good.’ —The Duke].

Yeah, maybe he was even quoting Duke Ellington. Lenny got asked that question over here in Germany all the time: ‘How do you mix E–Musik and U–Musik?’ And he would just shrug his shoulders and say, ‘Look, there’s good music and there’s bad music.’ In our time, God bless Wynton Marsalis: we somehow laundered Gershwin into this quasi-classical periphery, probably not as fundamentally as Gershwin’s intent ever was — but the person who we’re way behind on and just starting to gain ground on is Duke Ellington. It’s absolutely astounding the pieces this guy wrote. Looking back, I am sure it had a lot to do with racism in America, but clearly we are gaining serious ground on that now. I hate to be a Pollyanna-positive kind of guy here, but I think we’re in some very exciting musical and artistic times and I think technology — as it has always been with classical music, the helping uncle of a struggling family — technology is breathing a quick and new orientation to classical music, maybe even more so than some other musical genres.

It has always seemed to me that poetry takes back language from advertisers —

Bravo.

— in the same way that art music reclaims music from advertising . . . and elevators and television and other media, wherever it is used to manipulate.

Look, I’m very concerned that we have lost a relationship to music as a language. It has become extremely gratuitous. And it’s not even the elevator problem, it’s actually a production problem, it’s actually in our own media. Whether it be musical theater or opera, music becomes the short-shrifted glue by which some sort of theatrical experience is happening. And that’s just not enough in the musical art form of opera. I agree with you, and I am always inviting someone in my world to take a break from the day-to-day, hour-to-hour informational tsunami that is on us all the time. We’re always getting quick impulses, quick bytes, quick information, and that’s fine, that’s modern life, that’s who we are. But there is another layer of us that lives in wonderful coexistence. It is not unusual to watch CNN or check your Blackberry and then walk in, sit down and listen to Shakespeare. Whether we can get the iPhone off before the first narration arrives is a debatable issue. But those are societal issues, a sociological phenomenon. I’m interested in this idea of changing brainwaves and saying, ‘No! You get to think about this now: slower, deeper, on your own terms, with your own avenues in.’ We speak so much of ‘a worldview’ or people finding their worldview. I think it starts on the inside. From that inside perspective we build a construct of what we believe to be our worldview.

And it seems to me that within arts and humanities, music is so incredibly important in understanding cultures if we are going to have a truly multicultural understanding of one another. If we are going to build respect, if we are going to actually put our weapons down, if we are going to have entrées and collaborations and economic assistance, we better damn well know who we are as a people — either ‘we’ approaching another, or ‘them’, whom we accept as a partner. I think we are fortunately in a time now where arts and humanities are gaining a new respect. It’s complete insanity that we left the arts and humanities off to be the higher end of the entertainment industry. They are as endemic to our thought process as business and economics and mathematics.

Whether it be musical theater or opera, music becomes the short-shrifted glue by which some sort of theatrical experience is happening.

I saw your Eugene Onegin at the Met this season, and there was a powerful moment, immediately following Onegin’s victorious duel, where he is changed onstage out of dueling garb into formal evening wear while the set gradually shifts around him: from the battleground, a ballroom emerges. All the while, the orchestra plays. In combination, these elements effected a very elegant and chilling passage of time. I was struck then at the importance of physically experiencing opera live, as it seems that the audience becomes an essential factor in the success of that passage-of-time equation.

Oh, without question! What you’ve just described is something that can only be truly experienced in the live forum. And, yes, we must even go so far as to say that regardless of the spectacular quality of HD broadcasts of opera — and I’m as big a fan as anyone, it’s an exponential augmentation of the opera world, it does wonders for the audience, it does wonders for the hardcore operagoer who goes to the cinema and says, ‘Oh my God, I had no idea it could be this exciting!’ — does that mean that opera of our generation is now the cinema? Of course not. All multimedia is simply an augmentation to an art form that in its truest form is experienced live, in whatever theatrical environment — small-town, big-town, it doesn’t matter. The art form is a musical art form and it is an acoustical art form, meaning the acoustic of visuals, the acoustical, experiential moment in the theater. I don’t think that diminishes any multimedia experiments; in fact, quite the contrary. Part of the augmentation can also be a mutation into a quasi-sub-art form. Some things could be described or justified or manipulated more explicitly onscreen than they could be onstage, but again, it would not exist in juxtaposition or on its own were it not for the public and personal experience within the theater. So, your remark is very apropos and it begs a very important discussion in our time.

And that’s something that we’re doing very, very well in America and it transcends a lot of the inherent distance problems in America. At first I think a lot of ‘smaller’ opera houses felt that their public would diminish because of the cinema or the Met versus coming to local opera, and it sounds like that demographic might have had reason for concern, but only very briefly. Now it’s starting to flip around and we are seeing evidence that in fact the HD — from several theaters, but predominantly the Met — is increasing overall awareness and opera houses are actually getting a bump out of it, and whatever we can do to make that circle complete, I think we should.

related...

-

When the Shoe Fits

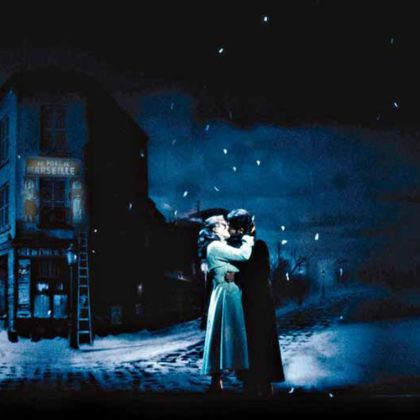

Prokofiev’s Cinderella is much more than a charming retelling of the beloved fairy tale.

Read More

By Thomas May -

Respighi: Beyond Rome

Respighi’s set of variations is cast away for his more

Read More

‘Roman’ repertoire.

By David Hurwitz -

A Simple Love Story

It’s no accident that Puccini’s La bohème remains the most performed opera.

Read More

By Robert Levine