Truth in Music

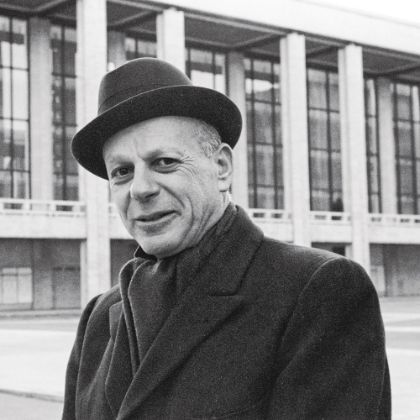

Gidon Kremer delves into the roots of musical expression.

By Ben Finane

gidon kremer, now sixty-three, remains a peerless violinist. Eight years ago, I heard him perform a marathon of Bach’s Sonatas and Partitas with a single intermission. This concert had such a profound effect on me that I was unable to write my assigned review for fear of cheapening the music with my words. (A version of the experience can be had via his 2002 recording of the repertoire on ECM.) Kremer has two new albums with his chamber orchestra, Kremerata Baltica: Hymns and Prayers (ECM) and De Profundis (Nonesuch), both released this fall. The violinist spoke to me from Croatia about Bach, his orchestra and his sound.

I have to tell you that one of the greatest concerts I have ever heard was your performance of the Bach Sonatas and Partitas in 2002 at St. Paul’s Chapel at Columbia University.

[Laughs.] Thank you for remembering it! It was a memorable one for me, too, as I played this concert live only four times — twice in Europe and twice in the United States. I was dealing with Bach after an intermission, you could say. I had recorded my first cycle around 1980; almost a quarter century later, I took on this adventure. It’s one thing to play this in the studio, quite another live in concert. It was a big challenge for me — and for the audience. I realized during the preparation for these concerts and traveling with the scores and practicing that Bach is a wonderful companion. When you are talking to Bach, you are never alone. There are so many ideas, feelings, spiritual things; Bach returns your efforts to come closer to him. There is always something to hold on to. Not every composer is able to give you this feeling; I often return to Bach. Most recently, I did so by asking ten contemporary composers to do arrangements of Bach pieces played by Glenn Gould for strings. I premiered a cycle of these pieces some months ago with Kremerata Baltica called “The Art of Instrumentation.” This hour-long cycle gave us the possibility of looking at Bach from the point of view of our day and gave another perspective of how deep and important is the music of one person — who seems to be from a different planet.

Does your heavy involvement with and study of Bach affect your playing of contemporary classical music, too?

Probably. When I did this Art of Instrumentation cycle where I had to deal with many different approaches by contemporary composers, each with his way of hearing Bach — his sounds and colors, the intrigue of a game in the fugue — each had his approach to Bach’s energy. And here you learn so much about music because after playing an hour of these orchestrations in recital, you realize that every bar is music; it doesn’t matter who orchestrated it. It’s still Bach and each of Bach’s statements is always so full of content, always with dedication to some more important things than humble us. You learn that this is the substance of music itself. Therefore, dealing with contemporary composers as such — and not just when they orchestrate Bach — you measure how much each of them is preoccupied with techniques, or how much a contemporary composition is searching for the substance of a statement, or how much of a signature a contemporary composer has. So I think Bach was and remains one of the personalities by which any jewel or fake in music making can be measured. He’s not the only one, of course. Recently I have been entering the chambers of Beethoven more intensely, playing more and more his late quartets. And he is another composer who didn’t allow any cheap stuff to be part of his work, while many composers in history mingled with an intellectual approach as simply an intellectual approach or simply pleasing the audience and trying to be sufficiently entertaining. I don’t think great composers were from this breed. And Bach would be one of the columns upon which all music stands.

It’s been thirteen years now with Kremerata Baltica. I imagine it has been very energizing for you to tackle great new work with young players.

For sure! It’s a steady group; more than half the players now also started with Kremerata. I always encountered a very sincere reaction and they are still very young. The average age is around twenty-nine; when I started, it was twenty-two. Dealing with young people is refreshing and it keeps you young yourself. Here and there, there are conflicts arising from this fresh and inexperienced approach, but this freshness also provides motivation to search further because experience is not always wisdom: experience can be quite a burden as well. So here we are dealing with some naïveté and some sincerity and intuition, and we are permanently exchanging ideas — and it keeps me young, yes.

While so many violinists pursue a shiny tone, yours is unabashedly rugged, woody and so organic. I know it’s difficult to speak about something so ephemeral and personal as tone, but perhaps you could talk a bit about your sound?

You know, you just mentioned a word and with my limited English I want to speak to something, let’s say just catch the ball and throw it: ‘organic.’ Organic food. [Laughs.] And there is something very natural in it. I have always tried to be loyal to some inner truth of the [music’s] statement and I’ve never cared so much about the packaging of it. For me, it’s very important to remain truthful to the composer and I am always in search of the key to how a certain score has to be read, through which door you enter the statements by different composers. So I’ve never followed and still do not understand what is meant by people who say ‘You have just to sing on the instrument.’ Many instrumentalists are taught this way because there is a misunderstanding that an instrument should just imitate the voice, but the singing voice. The misunderstanding occurs because the instrument is a voice on its own and you have to explore all possibilities of what an instrument can give you. I want to hear an instrument speaking, speaking out something from the depths of the soul of the composer and adding my humble experience to it, my feelings. But I’ve never thought about packaging the sound and selling the masses the beauty of the sound itself, because for me it’s false, I would say bijouterie — artificial stones instead of looking for real ones.

In our shiny world everyone wants to be a star and wants to be recognized as such. We live in a world in which quantity matters more than quality, in which everyone wants to serve himself or herself more than to serve music. I am not saying I am alone confronting this weird approach — certainly there are other great musicians who, in their soul, do not participate in this game. I am just speaking out about a market that promotes all these false values because it has such an influence on people, and people do not understand that very often what they are offered is sheer mediocrity. The game is such that you can turn attention toward artists who look good, play brilliantly, but have nothing to say. This is a very dangerous development I am observing because there are so many brilliant, young instrumentalists who shine all around but they are so similar to each other. And I have always followed, for my models, people who were always recognizable, like the voice of Glenn Gould or the voice of Maria Callas, the voice of Astor Piazzolla — people who had a personality. People who you can recognize after twenty seconds and you know who it is. For me, as I live the last days of my life, it is important to speak to these values and not just participate in a game that is going on and on.

related...

-

Master Builder

His compatriots made institutions of their music. William Schuman made institutions.

Read More

By Russell Platt -

Beyond the Halftime Show

The American wind ensemble is quietly building a canon.

By Damian Fowler

Read More -

Sidelined, But Not Forgotten

The mysterious and wonderful music of Henri Dutilleux

By Menon Dwarka

Read More