The Rise and Fall of Cécile Chaminade

A hopeless Romantic in a time of progress

By Robert Hillinck

Most of my classmates hosted parties after graduating high school; I gave a senior recital. After a few months’ diligent practice I went onstage with my flute, and to the regal plod of a descending scale in the pianist’s left hand, opened the program with Cécile Chaminade’s Concertino, Op. 107. The piece’s melodicism, exuberance and conventional tonality make it a sure crowd-pleaser, and it has become such a staple in the repertory that we flutists call it simply “the Chaminade.” Its unassuming main theme draws listeners immediately to an idyllic pastoral sound world whose graceful lyricism flirts with the sentimental. Decorative passages pepper the score, stretching the player’s technical ability with fast-paced scales and arpeggios.

Cécile Chaminade (1857–1944) was a prolific composer who published more than four hundred pieces over her eighty-six years. These works cover a wide range of forms, from quasi-concertos with soloist and orchestra such as the Concertino or her Concertstück, Op. 40, to character pieces for solo piano; from themed symphony Les Amazones to an orchestral suite. She also wrote over a hundred mélodies for voice and piano as well as an opéra comique, a highly successful ballet, and a piano sonata. Chaminade’s compositional voice is tuneful and indicative of the French Romantic vogue in her youth, a time when Saint-Säens was at his peak and the most progressive composers, such as Wagner, were just starting to realize the full potential of the chromatic scale. But Chaminade’s voice did not evolve much over her lifetime, and by the heyday of the Impressionists and Richard Strauss, her compositions could be considered reactionary in their adherence to the harmonic language of the mid– and late–Romantic periods.

Joanne Polk recorded a solo-piano Chaminade album titled The Flatterer (Steinway & Sons), and first thought of the music’s lyricism when asked about the composer: “Her slow movements and much of the Sonata have such beautiful long phrases and melodies.” Her music is also technically challenging. Chaminade’s concert etudes, beyond testing a single technical demand, also boast “structure, architecture, beauty and harmonic interest,” which make them much more satisfying musically than the categorization “etude” might suggest. Most strikingly, Chaminade’s music displays a mastery of instrumental idioms that makes her works a joy to perform and to hear: “She writes wonderfully for the piano,” says Polk. “To me, composers break down into people whose music sounds harder than it is or whose music is harder than it sounds. All pianists and, I think, all instrumentalists favor music that sounds harder than it is, because the composer wrote so favorably, comfortably and idiomatically for the instrument.”

Joanne Polk recorded a solo-piano Chaminade album titled The Flatterer (Steinway & Sons), and first thought of the music’s lyricism when asked about the composer: “Her slow movements and much of the Sonata have such beautiful long phrases and melodies.” Her music is also technically challenging. Chaminade’s concert etudes, beyond testing a single technical demand, also boast “structure, architecture, beauty and harmonic interest,” which make them much more satisfying musically than the categorization “etude” might suggest. Most strikingly, Chaminade’s music displays a mastery of instrumental idioms that makes her works a joy to perform and to hear: “She writes wonderfully for the piano,” says Polk. “To me, composers break down into people whose music sounds harder than it is or whose music is harder than it sounds. All pianists and, I think, all instrumentalists favor music that sounds harder than it is, because the composer wrote so favorably, comfortably and idiomatically for the instrument.”

Born to a Parisian musical family in August of 1857, Chaminade began studying piano at an early age and began composing soon after, at the age of seven. Her studies continued privately with faculty from the Conservatoire de Paris — her father believed it improper for a young lady to matriculate formally in the school. Chaminade was also an accomplished performer, first making her name by giving recitals of her own music as early as 1878. Over the next decades, these recitals became international concert tours that saw her perform in Vienna, Belgium and Britain, where she became a favorite of Queen Victoria. She also toured the United States, where her performances in Carnegie Hall, Symphony Hall, the Academy of Music with the nascent Philadelphia Orchestra, and venues throughout the Midwest inspired hundreds of women to found eponymous musical societies: “Chaminade Clubs.” Yet in spite of her international renown, Chaminade continued to find herself marginalized by the Parisian music world, enjoying more success in the provinces. Her creative output waned after the turn of the century, despite being the first female composer accorded the title of Chevalier in the Legion of Honor (1913), and her deteriorating health prevented her from touring in the 1920s and ’30s. After moving to Monaco, she died in 1944 in solitude and relative obscurity.

How can we account for this astonishing decline? According to musicologist Marcia Citron, who specializes in film, opera and gender, there are a slew of reasons. As per her father’s wishes, Chaminade did not attend the Conservatoire, thereby sacrificing traditional entry to the network of music professionals in Paris. This was compounded by her more conservative musical vocabulary, which actively adhered to the style of the 1860s and 1870s even as the cultural avant-garde began to favor markedly different styles. Finally, while even a brief survey stands as a testament to the diversity of Chaminade’s creative work, she favored her character pieces and mélodies, performing these works most frequently on her concert tours and turning to those small forms throughout the 1890s as her primary mode of musical expression. Although these pieces were popular in Britain and America, Chaminade found herself written off by the critical establishment as a composer of “salon music.” Critics used this term disparagingly in the twentieth century to suggest a piece was artistically derivative, marked by gushing sentimentality and empty virtuosic flourishes that were best consumed at home for the light entertainment of women.

These musical attributes became coded as “feminine” in a system of sexual aesthetics that pervaded music criticism during Chaminade’s lifetime. While her character pieces were denounced as salon music, dismissed for their “femininity,” her concert works faced criticism for being fraudulently “masculine,” as in this 1889 review of her Concertstück: “A work that is strong and virile, too virile perhaps, and. . . I almost regretted not having found further those qualities of grace and gentleness that reside in the nature of women.” The following, which ran in the New York Evening Post, moves from sexual aesthetics to blatant sexism in its review of one of Chaminade’s 1908 Carnegie Hall performances: “[Chaminade’s music] has a certain feminine daintiness and grace, but it is amazingly superficial and wanting in variety. . . . But on the whole this concert confirmed the conviction held by many that while women may some day vote, they will never learn to compose anything worth while. All of them seem superficial when they write music. . . .”

‘But on the whole this concert confirmed the conviction held by many that while women may some day vote, they will never learn to compose anything worth while.’

This kind of criticism was not strictly reserved for female composers. Chopin wrote scores of short works for piano, many of which are sentimental or strewn with his signature decorative flourishes. However, late nineteenth-century music critics took great pains to rehabilitate Chopin’s music, stressing that this was only one facet of his compositional genius by pointing to the rest of his oeuvre, and suggesting that his more sentimental music be played with more manly vigor. Even Arthur Rubinstein congratulated himself for disassociating Chopin from salon music. Chaminade’s champions, on the other hand, were few and far between. “I think every composer needs an advocate,” Polk tells Listen. “It’s hard to be a composer in the time that you’re living. Normally composers get a lot of attention after they’ve died. But to be female and to deal with some of the gender stereotypes is an additional struggle... she was battered by critics right, left and center — and fell into oblivion because of it.”

Chaminade’s star faded in the light of such negative press, and her concert works remain largely overlooked beneath the remarkable output of character pieces and mélodies that contemporary critics so reviled. This misjudgment has proved tenacious, persisting even in the 1980 edition of the New Grove Dictionary of Music, which asserts that “notwithstanding the real charm and clever writing of many of Chaminade’s pieces, they do not rise above drawing room music.” Polk, who first discovered Chaminade by accompanying flute students on the Concertino at the Manhattan School of Music, has enjoyed getting to know the rest of her works and insists that Chaminade’s music stands up to any test. “I feel very strongly that her music should not be given a listen solely because she was a woman. I think she should be listened to and revisited because she’s a wonderful composer.”

related...

-

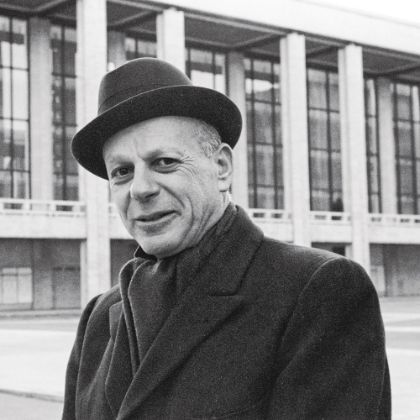

Master Builder

His compatriots made institutions of their music. William Schuman made institutions.

Read More

By Russell Platt -

When the Shoe Fits

Prokofiev’s Cinderella is much more than a charming retelling of the beloved fairy tale.

Read More

By Thomas May -

Respighi: Beyond Rome

Respighi’s set of variations is cast away for his more

Read More

‘Roman’ repertoire.

By David Hurwitz